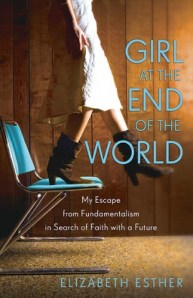

Elizabeth Esther’s Girl at the End of the World is finally out. I can’t remember the last time I read a book within two weeks of its release date. Of course, I have a soft spot for the religious memoirs of women, particularly when they manage to make their escape (I guess otherwise they wouldn’t be writing their experiences) from an unforgiving faith. Reading of the trials they have to go through to get there is far from enjoyable. But necessary. Often Bible-wielding males make the rules with a macho God behind them, and girls are abused in various ways so that the wrathful guy upstairs will be, well, a little less wrathful. I’ve read many of these accounts, and I worry deeply about the state of religion’s soul. Elizabeth Esther was raised in what she calls a cult, begun by her grandfather. This brand of fundamentalist Christianity taught the virtues of daily spankings of children, often beginning at about six months of age. The descriptions of how they used candy to tempt their children so that they could spank them to break their wills made me cringe. Evil wears many disguises, but none so effective as piety.

Elizabeth Esther’s Girl at the End of the World is finally out. I can’t remember the last time I read a book within two weeks of its release date. Of course, I have a soft spot for the religious memoirs of women, particularly when they manage to make their escape (I guess otherwise they wouldn’t be writing their experiences) from an unforgiving faith. Reading of the trials they have to go through to get there is far from enjoyable. But necessary. Often Bible-wielding males make the rules with a macho God behind them, and girls are abused in various ways so that the wrathful guy upstairs will be, well, a little less wrathful. I’ve read many of these accounts, and I worry deeply about the state of religion’s soul. Elizabeth Esther was raised in what she calls a cult, begun by her grandfather. This brand of fundamentalist Christianity taught the virtues of daily spankings of children, often beginning at about six months of age. The descriptions of how they used candy to tempt their children so that they could spank them to break their wills made me cringe. Evil wears many disguises, but none so effective as piety.

Religions are able to get away with quite a lot in a land of religious liberty. Elizabeth Esther proves that she’s made of some pretty stern stuff to have come through all of this, although she admits to still having panic attacks all these years later. She calls it Religious PTSD. She is right to do so. Although I grew up in a fundamentalism that scarred me for life, it wasn’t with the physical beatings that members of her grandfather’s religion doled out. When Elizabeth Esther describes the tendencies she has, the hyper-awareness of threat, I know that I am nevertheless still reacting the same way in my own life. After my fundie upbringing, I had the misfortune to be employed by a different kind of literalist religious institution. Faculty whispered about the new malady coming out of the Gulf when we started to develop nervous ticks and odd quirks after being kept under constant threat. When I contact many of my former colleagues I can still tell we were badly damaged there. Some religions, as Nietzsche long ago recognized, are life-denying to the point where a soul death would be more merciful. And yet we carry on.

Elizabeth Esther ends her book with a reluctant escape to Catholicism. She notes that even it doesn’t exist without its problems. We are, however, religiously evolved beings. It is in our constitution to seek the solace of communal worship, or at least a kind of spiritual solidarity. And there are those who will take advantage of people who simply seek their sense of self-worth from authority figures who claim to have it all worked out. Disproportionately those who are made to suffer are women. The Bible, although it cannot be blamed on the abuses heaped upon it in the name of the Judeo-Christian tradition, conveniently emerged from a patriarchal society. In the hands of some men it becomes an implement of torture. And many are left far poorer in life for having encountered this particular form of demon disguised as an angel.