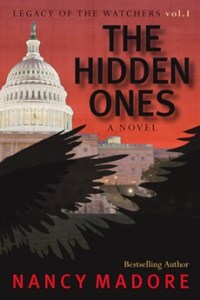

Angels, demons, djinn, watchers, giants, and a healthy dose of fantasy pervade Nancy Madore’s novel, The Hidden Ones. In this present world where, I’m told, the supernatural is irrelevant, it is pleasant to come across a work of fiction that delves so deeply into the pagan roots of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Monotheism does have its own skeletons in its capacious closets. Madore is a novelist who insists on prying open those doors long shut, and spinning a tale that involves first responders, shady military officers, and a band of rather hapless archaeologists. And Lilith. Throughout the story Madore comes up with clever etiologies for stories that will appear in canonical form much later, and at one point I couldn’t help wondering if the screen writers of Noah had read her book. Well, actually, The Hidden Ones is the first of a trilogy, Legacy of the Watchers. I’m sure the next two books will contain many surprises as well.

Angels, demons, djinn, watchers, giants, and a healthy dose of fantasy pervade Nancy Madore’s novel, The Hidden Ones. In this present world where, I’m told, the supernatural is irrelevant, it is pleasant to come across a work of fiction that delves so deeply into the pagan roots of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Monotheism does have its own skeletons in its capacious closets. Madore is a novelist who insists on prying open those doors long shut, and spinning a tale that involves first responders, shady military officers, and a band of rather hapless archaeologists. And Lilith. Throughout the story Madore comes up with clever etiologies for stories that will appear in canonical form much later, and at one point I couldn’t help wondering if the screen writers of Noah had read her book. Well, actually, The Hidden Ones is the first of a trilogy, Legacy of the Watchers. I’m sure the next two books will contain many surprises as well.

The Hidden Ones put me in mind of Michael Heiser’s novel, The Facade. Both take on the mythology of the Nephilim, the fallen ones about which the Bible tells us enough only to leave us hungry. The early chapters of Genesis are like that. There’s so much going on that those of us reading it many centuries after it was written are left wondering what the full story was. The writers of the Bible had no compunction to disbelieve in monsters and beings beyond the human ken. Nor does the Bible attempt to systematize them in any sustained way. These creatures just are. As the old saying goes, however, fiction has to make sense—those who write with gods and angels have to make them fit into a system.

No doubt, the uncanny occasionally intrudes upon our rational world. The Hidden Ones presents one such intrusion that, ironically, takes some of the fact of the Bible while leaving the theology suspect. We know that even before the Hebrew Bible was complete ancient scribes were attempting similar things. The book Jubilees, for example, tries to fill in some of the unanswered questions of Genesis, including the watchers and details of the flood. Jubilees, however, never made it into the Bible thus depriving canonical status to the backstory that demonstrates how religion often chooses for ambiguity, leaving it to theologians to bring it all into a system. And novelists. And among those novels that tread where even J, E, P, and D quail, is The Hidden Ones.