The first few weeks of May are peppered with holidays, some religious, some secular. As my regular readers know, I’ve been working on a book about holidays for kids, so I showcase a few pieces on this blog, on occasion. Instead of providing several posts on May’s holidays, I’m combining the first three special days into a holiday compendium for early May.

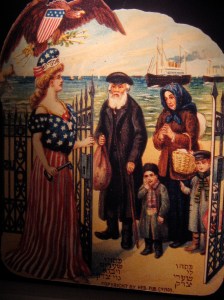

May Day (May 1) is, in origin, a religious holiday. It is an ancient, pre-Christian Celtic holiday called Beltane, it celebrates fertility, and it is a day that workers throughout the world fight for fair treatment. Sometimes it is associated with Communism. So, where do we begin to unpack all that? To start with, May Day is a cross-quarter day (Groundhog Day and Halloween are two others). Cross-quarter days fall halfway between the solstices and equinoxes – the days that mark the change of seasons. Ancient Europeans believed that cross-quarter days allowed spirits of the dead and other supernatural beings into the human world, as can be seen in the Germanic Walpurgis Night (April 30-May 1). Although named after a saint (Walburga, d. Feb. 25, 779) Walpurgis Night has deep pre-Christian roots in northern Europe. It celebrates the coming of May, or summer, with huge bonfires lit at night. It Germany it was also called Witches’ Night (Hexennacht) because it was believed that witches gathered on Brocken mountain to await the coming of May. The Celtic May 1 is Beltane. For the Celts Beltane marked the start of summer and it was one of their two major holidays (the other comes around Halloween). Like the Germanic tribes, the Celts lit bonfires on Beltane. Druids would light two fires to purify those who would pass between them. In Ireland people would dress their windows and doors with May Boughs and would set up May Bushes. These were signs of the returning fertility of the earth. This tradition survives in parts of the United States in the form of the May Basket. May Baskets are filled with treats and are left at someone’s door. The tradition is to knock and run, but if you get caught, the gift recipient gets to kiss you! These days, however, an unexpected basket at the door is more likely to result in a call to the bomb squad, so let your sweetie know ahead of time if you plan to give a May Basket!

Today is Cinco de Mayo, and like most things Hispanic, it is misunderstood by many Angelos. Frequently Cinco de Mayo is represented as Mexico’s day of independence. What it actually commemorates, however, is a historic battle. Napoleon III’s French Army was in Mexico in 1862. These guys were in the state of Puebla where an outnumbered Mexican force under 33 year-old General Ignacio Zargoza actually beat them on May 5. In the States, Cinco de Mayo is becoming a day to showcase Mexican culture, kind of like St. Patrick’s Day is for Irish culture. The Battle of Puebla is not Mexico’s independence day – that falls on September 16 and often escapes notice in the United States.

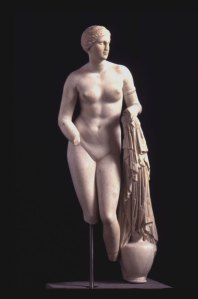

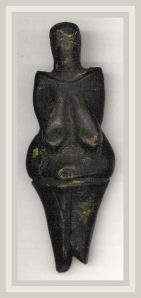

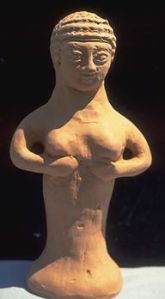

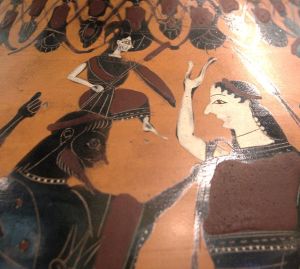

And, of course, Sunday is Mother’s Day. People around the world celebrate their mothers at various times of the year, but many don’t realize that this holiday goes back to the ancient Near East. Cybele was an ancient goddess associated with all things motherly. Originally from the Levant, the Greeks and Romans believed her to have been from Turkey (Phrygia). She had a festival day at the vernal equinox. Although there is no direct connection with the date or form of our Mother’s Day, it is possible that this annual recognition of an exceptional mother gave people the idea for Mother’s Day. Whatever it ancient origins may have been, Mother’s Day as we know it started in the United States as a protest against the Civil War. Many women believed war to be wrong. During the Civil War Anna Jarvis organized Mothers’ Work Days (as if they didn’t already have enough to do!) to improve sanitation for both armies. Julia Ward Howe wrote the Mother’s Day Proclamation, which was a document calling for the end of the war. The idea was to unite women in protest and bring the conflict to a close. After the war ended Anna Jarvis’ daughter (who had the same name as her mother) campaigned for a memorial day for women. Because of her efforts, a Mother’s Day was celebrated in Grafton, West Virginia in 1908. After that various states began to observe Mother’s Day, and President Woodrow Wilson made it a national holiday in 1914, ironically the year the First World War began. It is celebrated on the second Sunday in May.

For whatever spirits, political ideals, or goddesses you admire, May is the appropriate time to celebrate.