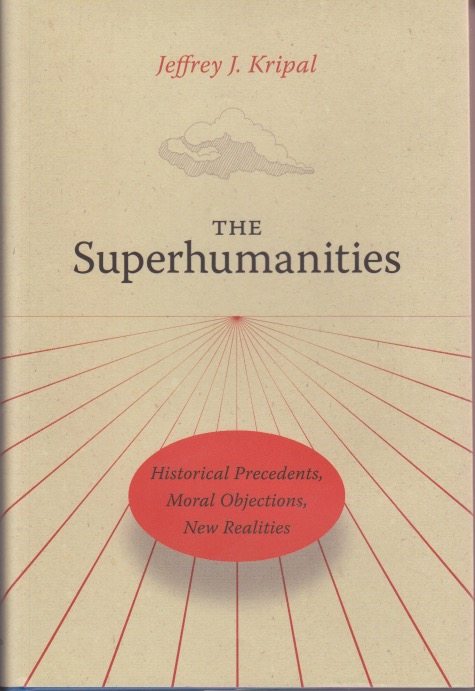

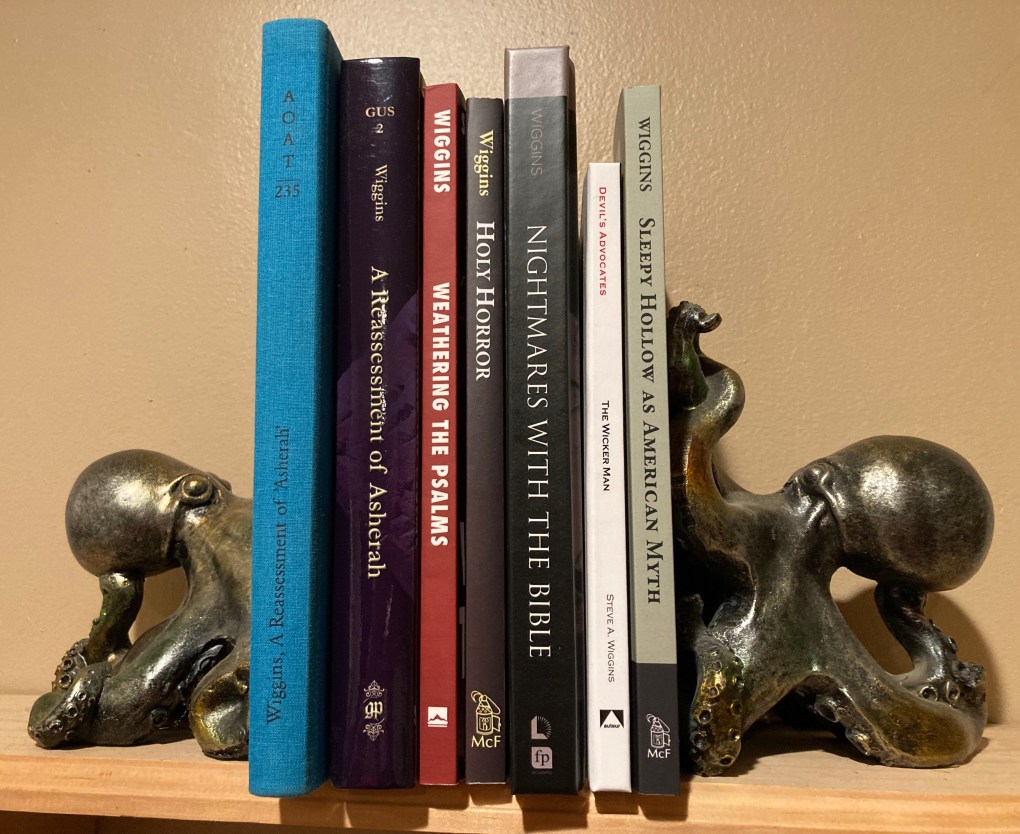

Here’s the thing: religion (or philosophy) is my life’s work. By that I mean that I can’t just casually encounter an important idea that impacts larger life and just let it go without wrestling with it first. As a professor that was expected. As a paid seeker of the truth, you dare not ignore new information. When I found myself unemployed with a doctorate in religious studies, the only jobs I could find were in publishing. Now, publishing is a business. And since I was a religion editor (still am), that meant that I had (have) to encounter new and potentially life-changing ideas and simply let them lie. I assess whether they might make a good book, but I’m not supposed to ponder them deeply and incorporate them into my outlook on life. Problem is, I can’t not do that. It’s an occupational hazard.

Some presses, I understand, won’t hire an editor with a doctorate in the area s/he covers. I think I can see why. It’s maybe a little too easy to get overly engaged. I work with other editors with doctorates in their areas. I don’t know if they have the same troubles I do or not. The fact is, other than religion/philosophy there aren’t many other fields that qualify as dealing with ultimate questions. History, for example, may be fascinating, but it’s not generally going to change your outlook on life, the universe, and everything. And so I find ideas that I need to keep track of since they might have the actual truth. But that’s not what I’m paid to do. I sometimes wonder what would’ve happened had I been successful in becoming clergy. They too are paid to wrestle, but they are expected to always end up on the side of the organization.

There are people cut out for a very specific job. No matter what else I do, I think about ideas I encounter. Especially the big ones. In the academy this was applauded. Elsewhere, not so much. The possibility of ending up in the job you’re made for isn’t a sure thing. It seems we value economics more than dreams. Or than systems that help people fit in with their natural inclinations. Then again, should I really be thinking about things like this when work is about to start? I should be getting my head in the game, shouldn’t I? But here’s the thing: religion (or philosophy) is my life’s work.