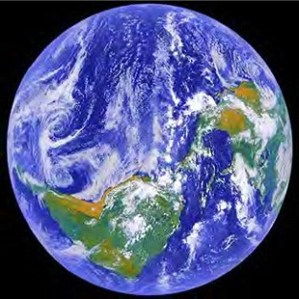

“Mankind [sic] has managed to accomplish so many things: We can fly!” The words are not mine, but, depending on whether he was standing or sitting when declared, the Pope’s or God’s. In his Palm Sunday sermon yesterday the Pope addressed the issue of technology. Acknowledging flight a mere century after it began is breakneck speed for the Roman Catholic Church, but the concern behind the sentiment is real enough. Can religious systems survive the full onslaught of the technological revolution? As one small sample of the larger picture, ethics must react to increasing advanced technological scenarios. Raymond Kurzweil’s proposed Singularity where human and machine are fully integrated is perhaps an extreme example, but by no means the most extreme. Without fully understanding the context, our technical ability has soared way beyond our capacity to foresee implications. Believe it or not, many people alive today cannot use personal computers, have no palms, no cells. Sounds like they might be living free.

Palm Sunday is a day of tradition, heavily freighted as the start of Holy Week (in the Western tradition; of course, many Christians think it is a little too early some years, but that’s for a different post). Fronds from actual trees are waved as the Pope speaks. In the crowd palms are also being utilized to send the news home that one is waving a palm in the presence of the Pope. Traditional Christianity can survive with only the most rudimentary of tools. Religion, from the available evidence, began in the Paleolithic Era – earlier, I am pretty sure, than even the first integrated circuit. With its iron grip on the human psyche, religion is not about to disappear. Instead, technology is either ignored or embraced by it. As long as religions rely on human participation, however, technology will need to be reckoned with.

The fact is technology has changed the perception of the world for many, especially in the western world. Even the revolution in Egypt earlier this year was conceived on the Internet. All the indications point to increased usage of technology rather than its imminent demise. Yet religious leaders still enjoin us to wave palm branches. Virtual Church websites abound where the faithful can wave electronic fronds and nary a tree will be harmed. Sermons, discussion groups, Bible readings, prayers – they can all be dispensed through wireless networks and modems. While many traditionalists turn from such ideas in disgust, it would behoove us all to pay attention. With the Vatican now onto the fact that we are flying, within mere decades we might receive a divine message on – oh, wait a minute – I’ve got mail!