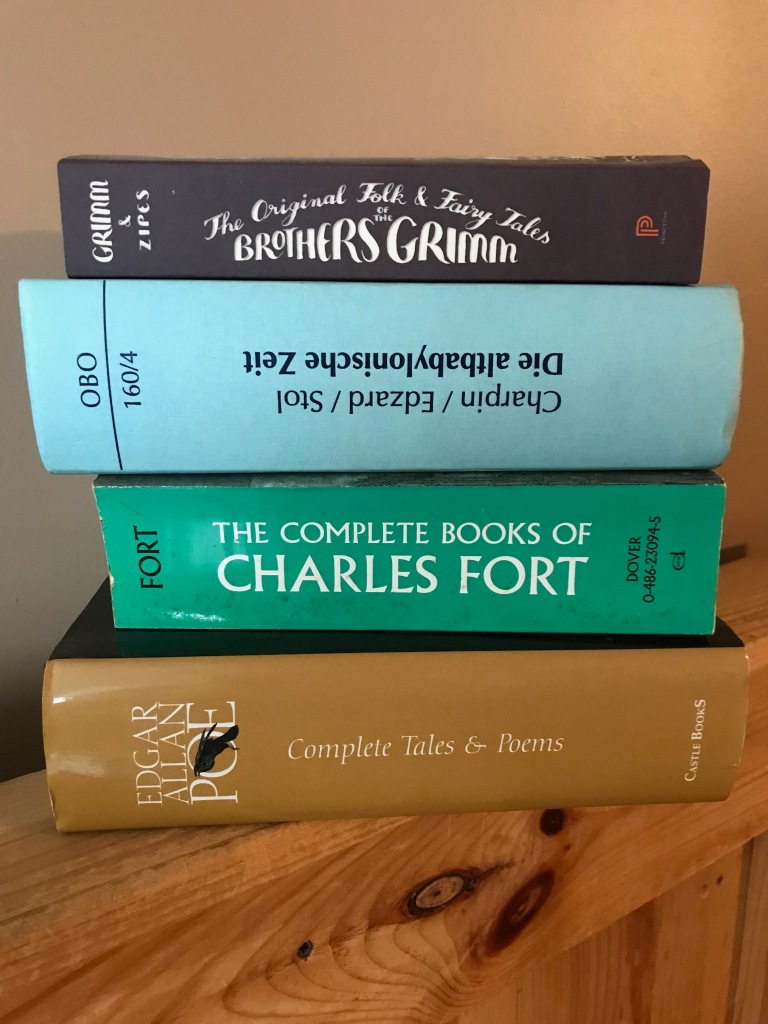

The more I read of and about Edgar Allan Poe, the more convinced I become that he wasn’t as associated with horror in his own mind as he has become. As one of the earliest American writers, he has become the icon of those who wrote on the dark side. His contemporaries—Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville—did as well, but it was Poe who became iconic. On a recent trip to Michaels to take in the seasonal ambiance, Poe’s presence was difficult to ignore. I wasn’t prepared to shoot a photo-essay (I’m not sure how they feel about such things in a store, in any case) so I didn’t photograph all the pieces. “The Raven” is frequently referenced, with typewriters with the poem emerging and large, ominous black birds about, but Poe himself also appears. There are, of course, painted busts of Poe.

But Halloween has grown more whimsical over the years. Arguably for my entire life it has been primarily a children’s holiday, but many have noticed that those of us who grew up with Halloween have retained adult interest in it. Part of this is no doubt commercial since the captains of industry have learned people will spend more on Halloween than any other holiday except Christmas (I do discuss this in my forthcoming book). And indeed, the Headless Horseman appears quite a lot as well. Irving, however, isn’t there on the ground. Poe is. The whimsical part comes through in showing the humor of the season. For example, although Poe is shown in the noble bust format, he’s also portrayed (fully clothed) on the toilet.

Finally, there were figurines of a fanciful tombstone of Poe. They even got the dates correct. Now, there’s more to be said regarding the comparison with Irving. You can find the Headless Horseman on the toilet as well (along with Dracula). You can find the Horseman in bust format as well. When it comes to tombstones, however, the fictional Ichabod Crane shows up alongside the nonfictional Poe. That casts a certain light on Irving’s most famous story. I’ll save that for another post, however, since authors are expected to repeatedly plug their books. I left Michaels strangely reflective. Poe-themed merchandise is fairly typical any given year, but since we’re having our first Halloween party in some years, and since I’ve been exploring Poe’s range as a writer, this clear abundance of Poe as an icon gave me pause. As if I were coming within view of the melancholy house of Usher.