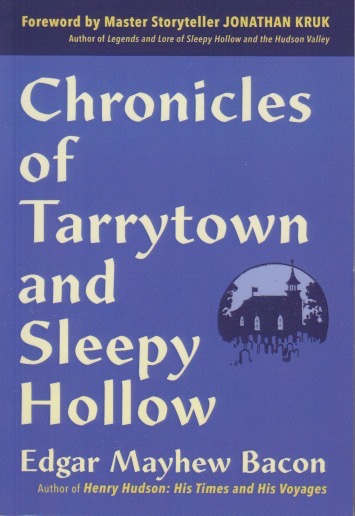

There’s a kind of charm to Chronicles. I don’t mean the biblical book, but rather Chronicles of Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow, a book published in the 1890s by Edgar Mayhew Bacon. A somewhat poorly organized volume, you get the sense that Bacon had more curiosity than literary ability, but that didn’t prevent him from leaving a valuable record. What’s more, other accessible books like it tend not to exist or be easily found. There’s definitely a reason to write so that the average person can read your work. I didn’t spring for an original edition on this one, as much as I love old books. Nevertheless, the material’s still old and that’s what counts. At least to someone with an historian’s point of view.

What really caught my attention here was Bacon himself. Who was he? His book was from that era of “you should believe me because I wrote a book about it,” but modern critics want to see credentials. Although search engines are often good, if you’re looking for information on an obscure author (such as yours truly) they’re going to try to sell you something first. Books, in the case of those of us who write. If you scroll down far enough you’ll learn that Bacon was born in the Bahamas in 1855. He wrote, it seems, five books. He doesn’t have a Wikipedia page and I looked him up because (in addition to basic curiosity) he at times appears to be a bit of a curmudgeon. He was only about 42 when this book was published, however, but writes like a long-time resident, slightly jaded.

Bacon was mostly a place writer. His non-fiction books focus on places he lived or knew. His educational history isn’t easily discovered, and again, the modern reader wants a degree (preferably three) to show that one can be a proper historian. He lived in an age, however, where gumption to write and complete a book likely meant finding a publisher. The internet has changed that, probably forever (or at least as far as we can see). It’s a buyer’s market for publishers. But still, Chronicles of Tarrytown was brought back into print and was made available again, in an affordable paperback. It contains some second-person history, closer to the events than we currently are, and a few legends as well. It can’t be relied upon for history as we know it, but it can still offer a bit of charm for those curious about yesteryear.