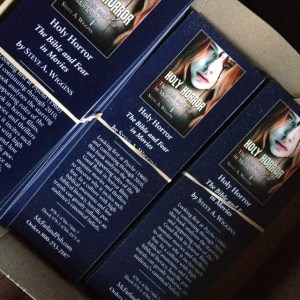

Progress continues on Nightmares with the Bible. Despite pandemic conditions, I received a happy email last week telling me that the manuscript had been transmitted to production. If you don’t work in publishing that probably sounds like a pretty simple step, but in reality it’s immensely complicated. The job of many editorial assistants is often just making sure books get through the transition from author to publishing engines safely. Since Lexington/Fortress Academic is short-staffed at the moment (publishing is a “non-essential” business), they ask authors to take on additional responsibilities. One that they passed on to me was to find people to endorse my book. Fortunately I’ve got star series editors who agreed to take on the task, sparing me from going to someone and saying, “Um, hi. Would you like to say nice things about my book?” I’m shy that way.

That doesn’t mean that I’m not excited about the book. It came about in an odd way, but like any parent an author loves her or his books, even if they aren’t quite what you expected. Getting a fourth book published is kind of a hallmark for me, especially since I spend a lot of time on the websites of successful academic colleagues older than me that haven’t reached that benchmark. Publishing books, for me, is a kind of validation. The original ideas of editors aren’t much valued, either in publishing or in society at large. Who cares what an editor thinks? Put that same person in a college and s/he’s a superstar, eh, Qohelet? So I sit here like an expectant parent, wondering what the book will look like although I already know what I’ve put into it.

Nightmares was never meant to be a research book. Indeed, Holy Horror was written with an eye toward trade publication. I’ve been working on my next book project (which I’m keeping under wraps at the moment for fear that someone with more time might get to it first, since there’s no getting the genie back in the bottle). Before too many weeks have passed I’ll need to brush off my indexing skills (in as far as I have any), and get proofs submitted. I’m afraid I’ll miss the coveted Halloween launch yet again with this book. “Scary topic” books always sell best in September/October, but if you miss it, the next year you’re old news. Like an anxious parent I sit here and wait because at this point things are literally out of my hands.