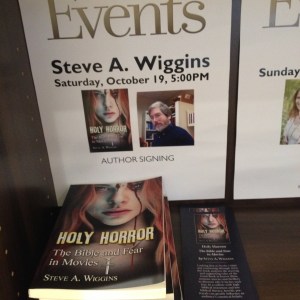

Publishers these days are all yammering about being “digital first.” Now, I use technology when I write these days, despite the fact that I am coerced to shut down programs at 3:30 a.m., my writing time, because tech companies assume people are asleep then and that’s when upgrades happen. Still, even as an author of the modest academic sort I know the unequalled thrill of seeing that first printed copy of my book. Authors live for that moment. It’s our opiate. Publishers don’t understand that. Five years back or so I had a novel accepted for publication. (It never happened, but that’s a long story.) At one point the publisher changed its mind—post-contract!—and decided that my story would be only an ebook. They tried to make me feel better by saying they thought it would do well in that format.

Who wants to hold up a plastic device and say “Look what I wrote!”? It makes about as much sense as smoking a plastic device. No, writing is intended to lead to physical results. Even those of us who blog secretly hope that someday someone will say, “Hey, I want to publish your random thoughts as a book.” As long as it’ll be print, where do I sign? In some fields of human endeavor there are no physical signs that a difference has been made. Is it mere coincidence that those who work in such fields also often write books? I suspect not. Writing is a form of self-expression and when it’s done you want to have something to show for it. All of that work actually led to something!

Since I work in publishing I realize that it’s a business. And I understand that businesses exist to be profitable. I also know that technology sits in the driver’s seat. Decisions about the shape of the future are made by those who hold devices in higher regard than many of us do. I’m just as glad as most for the convenience of getting necessary stuff done online. What I wonder is why it has to be only online. The other day I went looking for a CD—it’s been years since I bought one. At Barnes and Noble about all they had was vinyl. I’m cool with records, but my player died eons ago. I had to locate a store still dedicated to selling music that wasn’t just streamed or LP. That gooey soft spot in the middle between precomputer and 0s and 1s raining from the invisible cloud. I went home and picked up a book. Life, for a moment, felt more real.