Scientists tell us the earth is slowing down. It’s only by a fraction of a fraction of a second, but like a top set spinning these endless revolutions can’t go on forever. Although the evidence all points in this direction, it feels like it’s speeding up. How else can I account for the apparent loss of time I’ve been sensing? Let me contextualize that. I’ve been attending the Society of Biblical Literature and American Academy of Religion annual meeting since 1991. That first meeting in Kansas City’s acid-etched in my friable consciousness with the long hours waiting for interviews that never came and no mentors to show me what to do. Those three-and-a-half days stretched on into an endless Tom Sawyer summer. I was anxious to get back to my wife in Edinburgh to and finish my dissertation. Fast forward a quarter of a century.

My days are now filled with back-to-back meetings. Normally by now I’d have had a leisurely perambulation among the bookstalls (where I spend all day) taking in the volumes the competitors publish, noting what I need to read. Instead, the time has been shortened. I have to keep a constant watch on my watch for the next appointment. Hearing about new books being born rather than tending the infants that surround me. We are a thriving population of readers here. Although it looks like a large crowd, I know that in reality we don’t make much of a dent. Boston’s big enough to absorb us and all our feverish ideas. When wakefulness arrives at my usual New York commuting time, even the nights seem to be shorter. Where has the time gone?

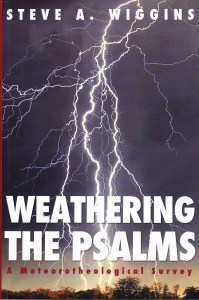

Most of those I meet have no idea I write books of my own. It was a process started long before the conferral of a diploma from a university far away. The earth is spinning in that direction, I’m told, so I should be in the tailwind of Edinburgh all the time. I’ve grown old with some of these colleagues. Those I’ve known since I was a young man, thinking he knew something about life, learning how little he really knew in this very city. I’m pretty sure I know even less now. The world, for example, seems to be speeding up to me. In fact I know it’s slowing down. Days are growing longer, but there is ever more yet to do. And all I want to accomplish right now is to walk around a bit and browse the books that others have written. I’m absolutely sure the earth is indeed speeding up.