There’s an old tradition regarding demons that even discussing them is dangerous. This was certainly in my mind as I wrote Nightmares with the Bible, as the topic is an uncomfortable one, at best. A recent story by Paul Seaburn on Mysterious Universe references this danger in the title “Exorcist Claims ‘The Exorcist’ and Other Horror Movies are Sources for Actual Demons.” Others have made similar suggestions that merely mentioning a demon is a form of summoning. The post focuses on Fr. Ronnie Ablong, a Catholic priest in the Philippines, and an exorcist to boot. Fr. Ablong claims that a number of recent cases involve fictitious demons from horror movies that possess those who watch them. This is scary by implication and indeed is similar to what I learned growing up.

One of the things researching Nightmares revealed was that demons in the ancient world come in many varieties. There wasn’t one origin story behind them and ideas that make it seem that way had to evolve over time. Of course, you can’t write a book like that without watching the movies and reading lots of books about demons. It is a creepy thing until you start to reach the point where the material starts to break down. In the case of Fr. Ablong, the demons come from movies, but often movie demons are based on ancient grimoires that name various entities. The real question, and one which Seaburn raises, is whether such demons are real. Given that we don’t know what demons are, and that some of the movies mentioned use made-up demons, such as Annabelle, it becomes suspect.

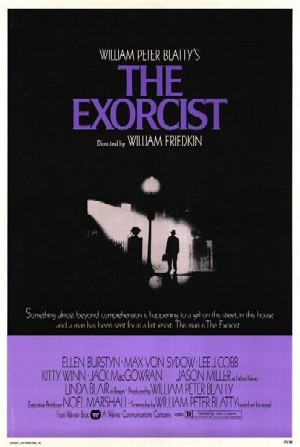

After finishing Nightmares with the Bible I was ready to put the subject aside for a while. I’ve got other projects going and it’s important to have some balance, even in horror watching. Still, the article caught my attention because it was one I’ve frequently heard—the danger of “opening doors.” Often this is done unintentionally. There’s no doubt that in the biblical world demons were frightening. They still are. Part of the reason is that they are so poorly defined. In many more recent treatments they’ve become somewhat secularized, but they are, by their nature, religious monsters. There is some truth to the Mysterious Universe story, however; our modern conception of demons goes back to the movie The Exorcist. This is something I discuss at length in Nightmares and I don’t want to give too many spoilers here. The topic, it seems, remains relevant even in our technological era.