Back at Nashotah House Episcopal Seminary, we were a closed community. Well, not completely closed, as much as some may have desired it. When a communicable illness came to campus it quickly spread. No wonder—we were required to all gather twice daily in the chapel, and there was the passing of the peace during mass. And the sharing of a common chalice. The germs of the Lord were readily spread. One of the faculty members would refer to the vector of the illness as “Typhoid Mary,” a rather sexist remark in the mostly male environment. Still, Mary Mallon came to mind as the current crises has settled in. “Typhoid Mary” was an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever. A working-class girl from Ireland, outbreaks of typhoid followed her in the various houses in New York City where she worked.

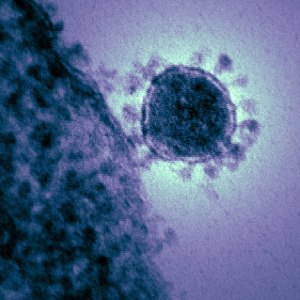

Photo credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH), via Wikimedia Commons

The current coronavirus outbreak in New York City seems strangely similar in some regards. Although COVID-19 is less likely passed by asymptomatic carriers, according to what I’ve read from the World Health Organization, it is still a possible vector. While out getting necessary supplies in the area I recently noticed store employees without gloves or masks, both of which I had on. One of us was underdressed. I went home, washed my hands thoroughly, and pulled my copy of The Andromeda Strain from the bookshelf. Self-medication can come in several forms. Some people still look at me funny for wearing a mask, but many other customers are now doing the same. The Center for Disease Control recommends it.

Before I’d ever heard of Nashotah House, I worked in a grocery store. I was a college graduate with facial hair that had to be removed. “Customers don’t trust a man with a beard,” I was told. Back then if you walked into a store with a mask on there would’ve been trouble. Contagion can drive you crazy. Nobody wants to be a “Typhoid Mary,” and yet it’s difficult to be out in public with a mask on. “Who was that masked man?” they used to ask of the Lone Ranger. From the theater and psychology I’ve studied, I know that hiding behind a mask can be a liberating experience. Aware that nobody knows who you are, you are free to act most any way you please. But this is different. Maybe it’s because my mask is made of a paisley-ish bandana, the kind old westerns show outlaws wearing. Or maybe it’s because of the guilt a religious upbringing so generously left with me. After all these years the old cliches are coming back to life.