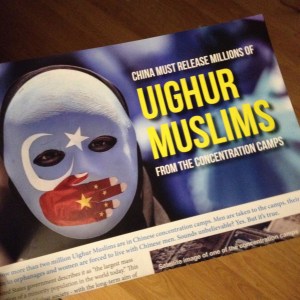

Recently, according to an ABC story a friend sent me, some self-righteous Catholics stole indigenous statues from the Amazon from a location in Rome. The statues had been a gift to the Pope and placed outside the church of Santa Maria in Traspontina. Like mass shooters these days, the Christians responsible filmed themselves doing this and shared it on social media. I’ve experienced a lot of religious intolerance in my life. I lost my job and my childhood to it, among other things. Stories like this are beyond sad because religion really does have the capacity to bring people together rather than to tear them into warring factions. Unfortunately it tends to draw in the hateful looking for excuses for their violence.

Not unrelatedly, I attended a church program on gun violence. Before this gets immediately blown up into “anti-gun,” please note—the program was about violence, not guns. During the Q&A after the presentation someone asked who the panelists were trying to reach, “preaching to the choir.” After that he admitted to being a gun owner and felt that his position was unfairly represented. Tension mounted. One of the panelists, the one who’d witnessed his first murder at age 11, and who’d spent time in jail himself, broke in and said “This is about violence, let’s not make it about guns.” I was struck by his focus and control. He’d told us earlier that if a gang member could be convinced to wait 24 hours before getting his gun after an insult or injury a shooting almost never took place. Violence is often a spur of the moment thing.

Not unrelatedly, I attended a church program on gun violence. Before this gets immediately blown up into “anti-gun,” please note—the program was about violence, not guns. During the Q&A after the presentation someone asked who the panelists were trying to reach, “preaching to the choir.” After that he admitted to being a gun owner and felt that his position was unfairly represented. Tension mounted. One of the panelists, the one who’d witnessed his first murder at age 11, and who’d spent time in jail himself, broke in and said “This is about violence, let’s not make it about guns.” I was struck by his focus and control. He’d told us earlier that if a gang member could be convinced to wait 24 hours before getting his gun after an insult or injury a shooting almost never took place. Violence is often a spur of the moment thing.

What’s so troubling about those who smirk as they film themselves doing violence, like stealing statues outside a church, is that this is not an impulse act. This is planned, hateful violence. It wears the mask of religion, often titled “orthodoxy” or “conservatism” but it is in reality simply a way of excusing your hatred. Ironically, the Jesus they claim to be following said, “Let the one without sin throw the first stone.” I guess we’ve got quite a few sinless conservatives out there, although I have to wonder if filming yourself might not count as pride. It used to be called a deadly sin, but who’s counting? Self-righteousness isn’t quite the same thing as vanity, although they sleep in the same bed. But let’s not get lust involved, once that happens there’ll be no telling one sin from another.