Among the constant topics of discussion, both in the academy and in its publishing ancillaries, is the loss of interest in religion. After a period of growth early in the new millennium, as measured by college majors, interest has dropped off and Nones are set to replace evangelical Christians as the largest religious group in America. The corresponding lack of interest in religion is extremely dangerous. I’ve often posted on the necessity of looking back to see where we might be going, and the further back we go the more we understand how essential religion is to the human psyche. My own academic goals were to get back to the origins of religion itself—something I continue to try to do—and I discovered that they rest in the bosom of fear. I’m not the first to notice that, nor have others been shy about using it to their advantage.

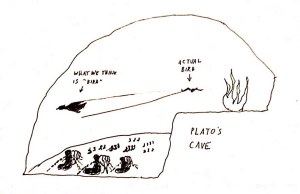

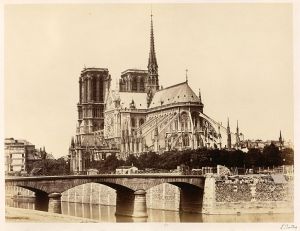

Lack of classical education, by which I mean reading the classics, has led us to an extremely tenuous place. More interested in the Bible, I followed the track to another ancient system of thought, but as I find out more about the religion of classical Greece and Rome, the more I tremble. You see, ancient Roman writers (especially) were extremely conscious of the fact that fear motivated people. In order to construct a steady state, they infused it with a religion based on fear and supported by said state. An overly simplified view would suggest that the Jews and Christians took their religion too seriously and refused to play the Roman game. When they wouldn’t worship the emperor (who surely knew he wasn’t a god) they threatened the empire. The response? A good, old-fashioned dose of fear. Crucifixion oughta cure ‘em.

The thing is, our American form of government, buoyed up by an intentional courting of evangelical Christians as a voting bloc, manipulates that fear even more stealthily than the Romans did. People ask me why I “like” horror. I don’t so much like it as I see its role as a key. It is a key to understanding religion and it has long turned the tumblers of the state. Ancient societies kept religion under state control—something the Republican Party has been advocating as of late. Why? Religion, based on fear, ensures the continuance of power. Those of us who watch horror are doing more than indulging in a lowbrow pastime. We are probing the very origins of religion. And we are bringing to light the machinations with deus. Let those who read understand.