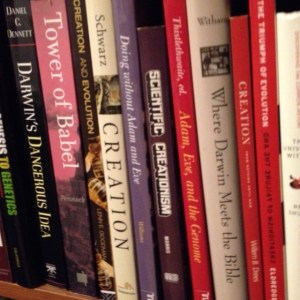

In the process of unpacking books, it became clear that evolution has been a large part of my life. More sophisticated colleagues might wonder why anyone would be concerned about an issue that biblical scholars long ago dismissed as passé. Genesis 1–11 is a set of myths, many of which have clear parallels in the world of ancient West Asia. Why even bother asking whether creationism has any merit? I pondered this as I unpacked the many books on Genesis I’d bought and read while teaching. Why this intense interest in this particular story? It goes back, no doubt, to the same roots that stop me in my tracks whenever I see a fossil. The reason I pause to think whenever I see a dinosaur represented in a museum or movie. When a “caveman” suggests a rather lowbrow version of Adam and Eve. When I read about the Big Bang.

The fact is evolution was the first solid evidence that the Bible isn’t literally true. That time comes in every intelligent life (at least among those raised reading the Good Book). You realize, with a horrific shock, that what you’d been told all along was a back-filled fabrication that was meant to save the reputation of book written before the advent of science. The Bible, as the study of said book clearly reveals, is not what the Fundamentalists say it is. Although all of modern scientific medicine is based on the fact of evolution, many who benefit from said medicine deny the very truth behind it. Evolution, since 1859, has been the ditch in which Fundies are willing to die. For this reason, perhaps, I took a very early interest in Genesis.

Back in my teaching days it was my intention to write a book on this. I’d read quite a lot on both Genesis and evolution. I read science voraciously. I taught courses on it. I’d carefully preserved childhood books declaring the evils of evolution. To this day Genesis can stop me cold and I will begin to think over the implications. When we teach children that the Bible is a scientific record, we’re doing a disservice to both religion and society. This false thinking can take a lifetime to overcome, and even then doubts will remain. Such is the power of magical thinking. I keep my books on Genesis, although the classroom is rare to me these days. I do it because it is part of my life. And I wonder if it is something I’ll ever be able to outgrow.