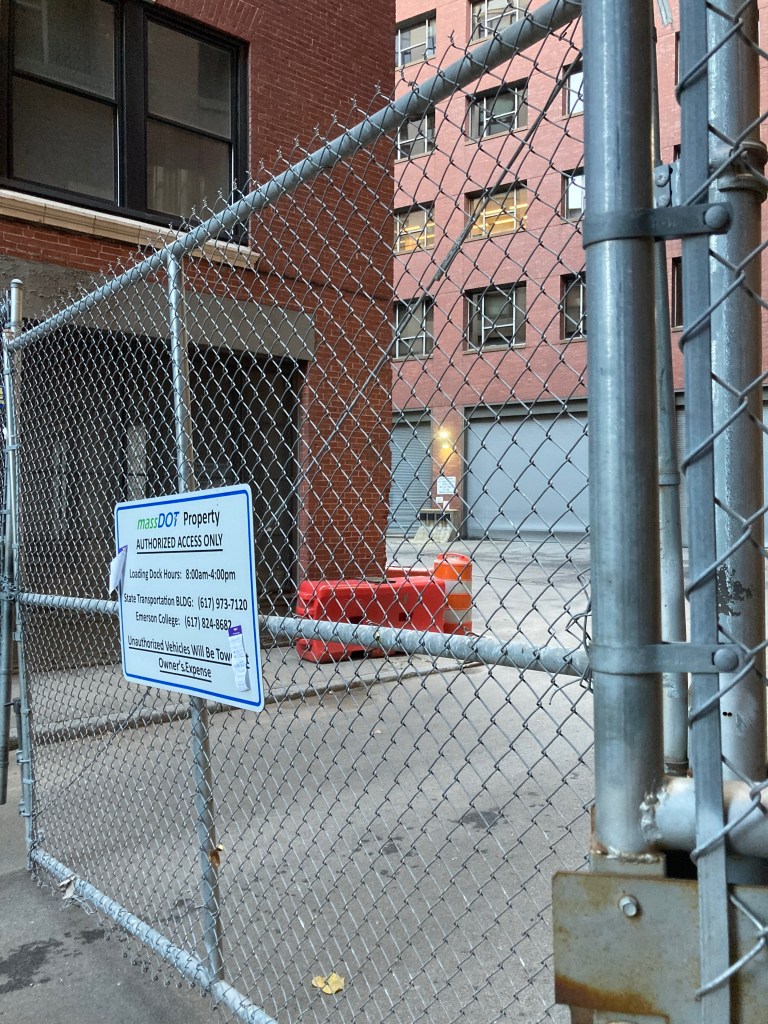

“Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds” is the unofficial motto of the United States Postal Service. Like many such traditions, it has an origin story. The saying was engraved on the James A. Farley Post Office Building in Manhattan. The building, which is an impressive one from street level, is no longer a post office. But the architect did not make up the inscription. It is adapted from the Greek historian Herodotus. Herodotus is known as both “the father of history” and “the father of lies.” In other words, his histories aren’t always, strictly speaking, historical. This is somehow appropriate given the saying’s pseudo-motto status. Especially when you open up the USPS website and see headers such as in the image below.

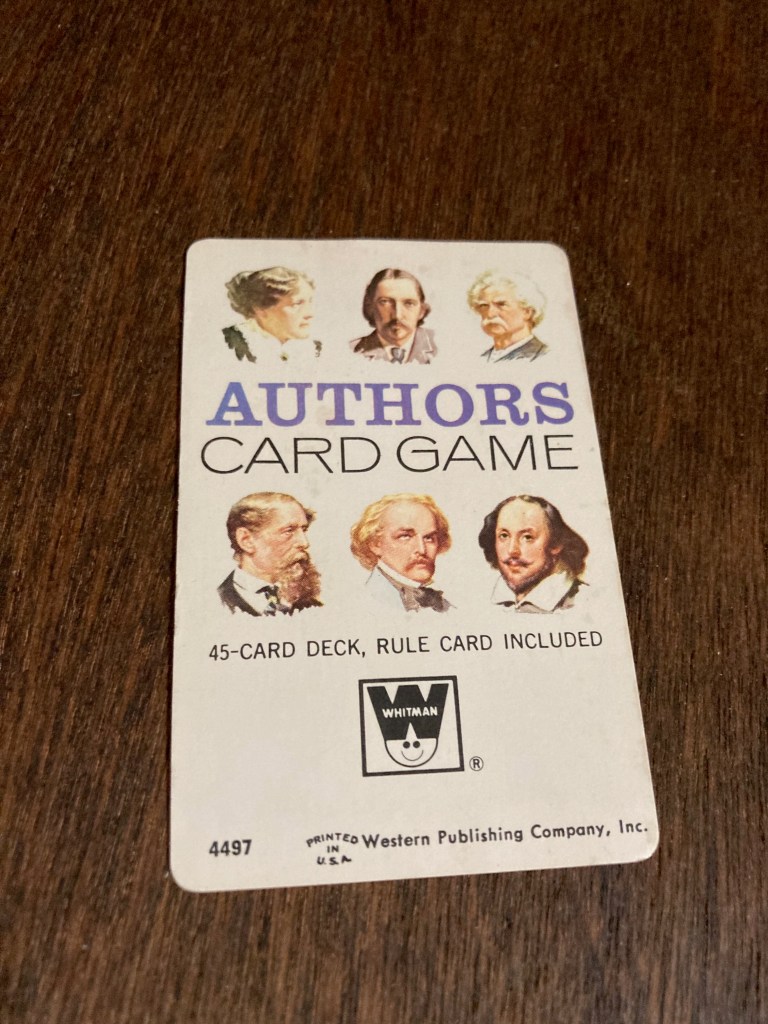

So snow and rain will stay these couriers after all. This is somewhat ironic, given that technology is supposed to make things so much easier. And this is in no way a negative reflection on actual postal workers. More than one of my family members has worked for the post office and I’ve even considered it myself. It’s just the jarring of expectations that’s disturbing. Around the holiday season, when the weather turns to its wintery mix, people grow anxious about their packages arriving on time. Cryptic messages often await those who visit the USPS website, tracking number in hand. A number that they supply to you cannot be found. Or a parcel that was literally three miles away has been sent to a distribution center seventy miles away for delivery. I pull old Herodotus from the shelf, looking for ancient wisdom. It’s not even snowing here.

The Farley Post Office Building is no longer a post office. Much of it has been converted into an extension of Penn Station, which is just across the street. I sometimes used to walk from Penn Station to the Port Authority, which is only a matter of a few Midtown blocks away. I had a glimpse of the new interior, briefly, darkly, from within an Amtrak train on its stop there on my way back from Boston. I had no letters or packages with me at the time, which is probably a good thing. You see, it was raining the last time I was there. Now, I’m no Greek historian, but I did manage to drive home that night, although the rain delayed me by about an hour and a half. No matter how noble our aspirations, the weather is still in charge. And I figure I’d better learn to be less anxious about deliveries come the holidays, and read Herodotus instead.