I discovered Jasper Fforde, as these things so often happen, at the recommendation of a friend. A writer of rare talent, he’s conjured a few meta-worlds where fiction is the subject of fiction. Probably best known for his Thursday Next novels, the premise is that fiction can be distorted by malevolent sorts within the Book World, which is like the Outside (our world) only much more interesting. The sole problem with series is that in order to follow the storylines, you need to be able to recall where things were left the last time. That’s complicated when you don’t read the books in order. I haven’t followed Thursday Next in sequence—I find Fforde’s books sporadically and pick them up when I do (I prefer not to buy fiction on Amazon, for some reason).

I discovered Jasper Fforde, as these things so often happen, at the recommendation of a friend. A writer of rare talent, he’s conjured a few meta-worlds where fiction is the subject of fiction. Probably best known for his Thursday Next novels, the premise is that fiction can be distorted by malevolent sorts within the Book World, which is like the Outside (our world) only much more interesting. The sole problem with series is that in order to follow the storylines, you need to be able to recall where things were left the last time. That’s complicated when you don’t read the books in order. I haven’t followed Thursday Next in sequence—I find Fforde’s books sporadically and pick them up when I do (I prefer not to buy fiction on Amazon, for some reason).

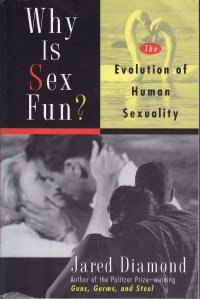

The latest installment I found is One of Our Thursdays Is Missing. It’s a bit more convoluted than the last plot I recall, but the writing is still good. In this story, which mostly takes place in Book World, the written Thursday Next has to find the real Thursday Next (who is, of course, also written, thus the “meta” I mentioned earlier). This is probably not the best place to start the series for neophytes. There was an interesting aspect, however, that I feel compelled to share. The majority of this novel takes place on an island dedicated to fiction, divided into different “countries” by genre. Just north of Horror and east of Racy Novel is Dogma. It’s just southeast of the Dismal Woods. This plays into the plot, of course, but the placement is interesting. As Thursday tells it, the full name of the region is Outdated Religious Dogma. Then I realized something.

Simply placing Dogma on this island plays into the idea that religious thought is fiction. There are other islands in Fforde’s world, including non-fiction. Dogma, of course, is not the same as religion. The definition of dogma is something that is incontrovertibly true, by the authority that states it. Problem is, nothing is inconvertibly true any more (if it ever was). When Christianity ruled Europe, such ideas became highly politicized. Indeed, parts of the world could well have fit into the Book World map. Fforde’s novel is really just for fun, and Dogma doesn’t play a major role in the story. That doesn’t prevent it, however, from being a legitimate point over which to pause and wonder. Fiction can be factual, but not in a dogmatic way.