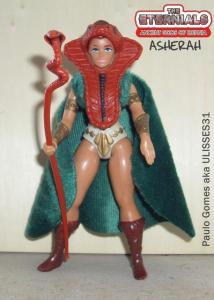

The goddesses Asherah and Astarte are sometimes confused, even by experts. Astarte, also known as Ashtart, Ashtarte, Athtart, and Astaroth, among other names, is the lesser attested of the two among the Ugaritic texts. Indeed, to read some accounts of the latter goddess, she becomes dangerously close to being labelled generic, the sort of all-purpose female deity embodying love and war, and sometimes horses. In the Bible Astarte lived on to become the bad-girl of Canaanite goddesses. Her corrupting ways were a conscious danger to the orthodox (as much as that is read back into the texts). She became, over time, literally demonized. It seems that originally she, like most goddesses, had a soft spot for humans. Since she wasn’t the one true (male) God, however, she had to be made evil. It is an unfortunate pattern as old as monotheism. One of my original interests in studying Asherah (not Astarte) was precisely that—the obviously benevolent divine female seems to have been chucked wholesale when the divine masculine walked into the room. Why? Well, many explanations and excuses have been given, but whatever the ultimate cause, Astarte lingered on.

In a local pharmacy the other day, I was looking over the Halloween tchotchkes. Amid the usual assortment of pumpkins, skeletons, and ghosts, I found bottle labels reading “Ashtaroth Demon Essence.” Although I’ve spent a good deal of my life cloistered in academia, I was not surprised by this. I know that in popular culture the goddesses of antiquity live on as supernatural powers, sometimes good, sometimes evil. Astarte, once depicted as the friend to at least some of the humans devoted to her, is now commonly a demonic force. The image on the bottle label, however, was most unflattering. I know, this is just kid’s stuff. Still, as I stood there among last-minute costume seekers and distracted parents, I knew that I was witnessing the influence of ancient religions in an unexpected way. Did any of the goddesses survive as a force for good? How could they when the only god was male?

We know very little about ancient Astarte beyond the fact that she took away some of the luster of the omnipotent (as now conceived) deity of the Bible. A jealous God, as Holy Writ readily admits, visiting iniquity down to the third and fourth generation. (That might explain a lot.) Prior to monotheism benevolence and malevolence could arise from goddesses as well as gods. Compassion, it was believed, was largely a feminine trait. Monotheism decided for the jealous male instead. We won’t find a bottle label for the Almighty, although the accouterment of the arch-enemy are everywhere evident this time of year. And speaking of the diabolical, the Ashtaroth Demon Essence, I noted, was available at a steep discount.