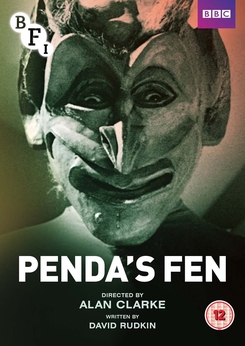

It’s one of those quirky British television plays that’s its own movie. It was part of the Play for Today series. I turned to Penda’s Fen after receiving some very distressing news, as a means of self-healing. (I may seem distracted for some time, please forgive me.) Sometimes considered folk horror, it really isn’t a horror film although it may be treated as one. The dialogue is heavily religious, involving a lot of theological discussion of Manichaeism, the “heretical” belief in the struggle between the powers of light and powers of darkness. It plays out through the maturing of Stephen Franklin, son of the local vicar who is, unbeknownst to himself, adopted. He also discovers his homosexuality as he begins to rebel against the strictures of his private school education. Underlying all this is the fact that he lives in Pinvin, in reality Penda’s Fen.

The story deals with the past interrupting into the present as Penda’s pagan kingdom never really fell. A local writer claims that there is an entire escape city beneath the British landscape to which those deemed “important” to the government are to be evacuated in case of emergency. In reality, the kingdom beneath, and overlapping, Pinvin is that of Penda. Penda was an actual Anglo-Saxon king and here he encourages Stephen to know himself—one of the mottos of the school. That knowing involves coming to question the conservative, Christian belief system he has wholeheartedly embraced. His adoptive father, the vicar, has broader beliefs, including the reality of other gods. Stephen discovers this and learns of his adoption, making for some heartfelt religious dialogue.

My reason for watching, apart from the much-needed therapy, was that it had been recommended as a piece of religion and horror. There are some horror moments, but generally it’s difficult to say whether they’re hallucinations of Stephen or they’re really happening. One is presented outside his viewing, which suggests that they are meant to be real. One involves a demon, but not the scary kind of The Exorcist, which had been released just a few months ahead of Penda’s Fen. In all, it’s a thoughtful movie, the kind you might expect when based on a play. Given the themes, I’m not sure it was the best therapy, but it did engage the religion and media dialogue. I hope to come back to it some day under better circumstances. The dialogue is worth engaging with more depth than I’ve been able to muster here right now and there’s much I still don’t understand.