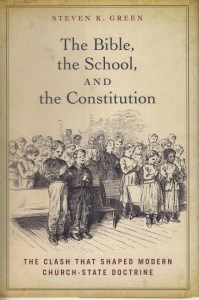

In the current presidential race, it seems, the Bible hasn’t been as large an issue as it has been in the past. Bluff, bravado, and bullying seem more the order of the day. Goliath rather than David. This makes me think of the varied uses that the Bible has had in American life. It has been used as a spiritual guide, a textbook, a set of moral principals, a grimoire, and a science primer, as well as a political playbook. It is versatile, the Good Book. It has been prominent in American society from the very beginning, but clearly its prominence is starting to fade. Not likely to disappear any time soon, the interesting question is how people use the Bible, often without reading it. This is what scholars call the “iconic book” aspect of the Bible. It is performative—it acts in a way that has an outcome, no matter what the intent of the user. As I’ve argued in academic venues, it has become a magical book.

Wondering whether this is a new situation or not (I deeply suspect it’s not) I’ve been reading about the Bible in early America. Almost all the reference material points to the “official” uses of the Bible—that by statesmen and clergymen (both classes of “men” in the early days) with almost nothing of how it was used in private. This question involves some exercise of the imagination since there are few data. Would not a family, struggling to survive, see in the Bible a powerful book? And would not a powerful book be capable of subverting the laws of nature? Reading about the witch trials in Salem, we see that thunderstorms and other “prodigies” were considered magical. Surely one could use the Bible for unorthodox purposes? There’s little to be said in the absence of evidence. The use of magic in the colonial period, apart from the trails of witches, was not unusual.How do we measure the ways the Bible was used when nobody beyond interested parties, such as clergy, wrote about it? Mr. Trump even tries to quote it from time to time, but since his citation that sounds like a joke opener, “Two Corinthians [go into a bar],” he seems to have let that hot potatoe drop. The Bible, seldom read, remains a powerful book. The source of its power, I suspect, is in its use by the common people. Many people are familiar with it, and believe in it. Some have even read it. It remains, however, one of the great mysteries among the early European settlers. We know they had their Bibles with them. How exactly they read them, when not under the eye of the preacher, we apparently have no way of knowing.