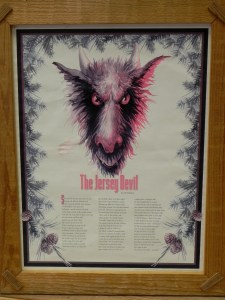

It’s the time of year for seeing things. I suppose that’s why there have been two supposed sightings of the Jersey Devil flying around the internet this past week. The credulous take these kinds of things for evidence, and the posters claim complete sincerity and who doesn’t want to believe? Still, the photos and videos fail to convince. It’s the time of year when we want to see monsters.

While the origin story of the Jersey Devil is one of the main strikes against it for sheer impossibility: Mother Leeds, who had twelve children, finding herself pregnant with a thirteenth, wished that it would be born a devil. The cursed child, meeting motherly expectations, came out a devil, flew up the chimney, and has haunted southern New Jersey ever since. The folklore elements are thick in this tale: the thirteenth child, the exasperated mother, devils in the woods. This doesn’t, however, suggest much confidence in the literal truth of the story. This traditional tale circulated in the same region where legitimately strange things were seen, especially around the turn of the last century. Every now and again the devil reappears in a present-day venue. At one time the Jersey Devil was even the official state demon of New Jersey.

The ease of use of photo-altering software has taken us further and further from the truth. It is an impoverished world that has no mystery to it, but the easily hoaxed world of Photoshopped monsters will cast doubt on all contenders, I fear, forevermore. We can no longer trust the veracity of the lens. Our world has become an electronic illusion. The creature spotted in the Pine Barrens can be more readily believed without photographic proof. The sober, shaken witness who can’t explain what s/he saw one dark night is more believable than a goat with wings or a stuffed animal on a string. Our religious sensibilities urge us to believe in the impossible. Our cameras urge caution. After all, internet fame is often the only kind available to those whose videos and photos go viral. The devil, they say, is in the details.