When World War Three starts I hope someone will let me know. You see, I barely have time to satisfy the needs of employers and tax collectors to get everything done in a day, let alone read newspapers. Or Facebook. I check my page, very briefly, twice a day and get on with the business that I’m assigned in life. But yesterday I had a notice from a high school friend that one of my teachers had died. Since I don’t name people I know here without their permission, suffice it to say I took a current events course with this teacher in either my junior or senior year. Then, as now, I didn’t read newspapers. Given the small town rags available in rustic regions, there was often not much mentioned beyond deer season and local tragedy anyway. Originally enrolled in the regular curriculum, several friends told me, “You’ve got to take Current Events! The teacher is great!” Those who’ve influenced my life for the good were great teachers, and despite my reservations, I took the class. When it came time to sign up for projects, I was a bit flummoxed. What did I know of current events?

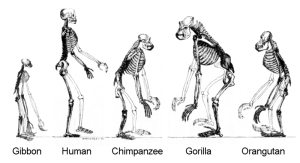

Our teacher kindly allowed me to offer evolution as a topic. It was occasionally in the news then. Six of us decided to debate the issue, three for, three against. My religion having held me in a headlock, I was the lead debater against evolution. The day for the debate came and we ran over the bell. Our teacher, with his usual calm wisdom, suggested we continue the next day. And the next. Three days of sometimes acrimonious debate and it looked, from my point of view, as if creationism had demolished evolution. How terribly naive I was. Ironically, I had just posted a piece on evolution yesterday when I saw the notice about my teacher’s demise. The position in my post was a sharp 180 from high school. It was a tribute to the love of education.

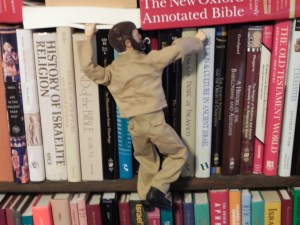

I was an outsider in high school. I literally lived outside of town and after school activities were not really feasible. We were poor and couldn’t afford extra-curriculars anyway. I wore a large cross on my chest and although I was shy, I felt that it said all I had to say. My teachers, to their eternal credit, let me explore. In college I learned about Fundamentalism. I had never heard the term although I grew up in it. Gently my teachers nudged me to think more deeply about things. Through three degrees delving more profoundly into the origins of religion, as well as humankind, I came to see the errors of my ways. Had I been forced in high school I would’ve fought back. Instead, a persistent, patient wisdom guided many of my teachers. I don’t know how they recognized that I might be worth salvaging, but they apparently did. They let me speak, they let me trip. Just as I was about to fall they caught me. And I hope, in my own small way, to repay this favor in kind.