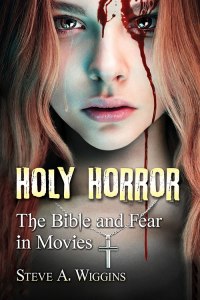

It’s not so much I’ve been away from monsters lately, but that life has intervened between them and me. Life can be scarier than monsters sometimes. In any case, the summer is when my mind turns back to haunting even as on the breaks during heat waves a whiff of autumn can be caught on the air of a July morning. Yes, we’ve past the solstice and days are getting shorter. Slowly, of course, but that’s what builds suspense. And there are local signs that I need to get my haunting in gear. It is finally time to get Holy Horror out of wraps and give the book a proper launch. Being published around Christmas last year was poor timing for a subject so readily coded for fall.

I received the welcome news this week that the Moravian Book Shop—the oldest continually operating bookstore in the country—will be hosting a book signing for Holy Horror in October. This is a fortuitous turn of events because when I first approached them with the idea the price of the book made the idea look unrealistic. But we’re now thinking of autumn, and with autumn comes Halloween. There have been a spate of horror films this summer, all of which I’ve unfortunately missed. Time, as Morpheus notes, is always against us. There does, however, seem to be a lively interest in the genre and the curious wonder what it has to say about what we believe. Horror loves religion, and indeed, thrives on it. So it’s been from the beginning.

October will also see the Easton Book Festival in this area. I will be on the program for that as well. While none of this is earth-shattering, these events represent the first successes in trying to build awareness of Holy Horror. This was a book written for a general readership, but not priced for one. Working in the academic publishing world, this is a phenomenon with which I’m all too familiar. Many colleagues offer to read and spread news about your book. It seldom happens, though. Academic presses can’t afford book tours (especially if they have to price books at $45), but these self-driven presentations are opportunities to spread the interest in ideas. That’s what those of us who write really want—to be part of the conversation. We’re in the midst of a heat wave here. It’s the height of summer. Even so, those who know about monsters can feel them coming, even from here.