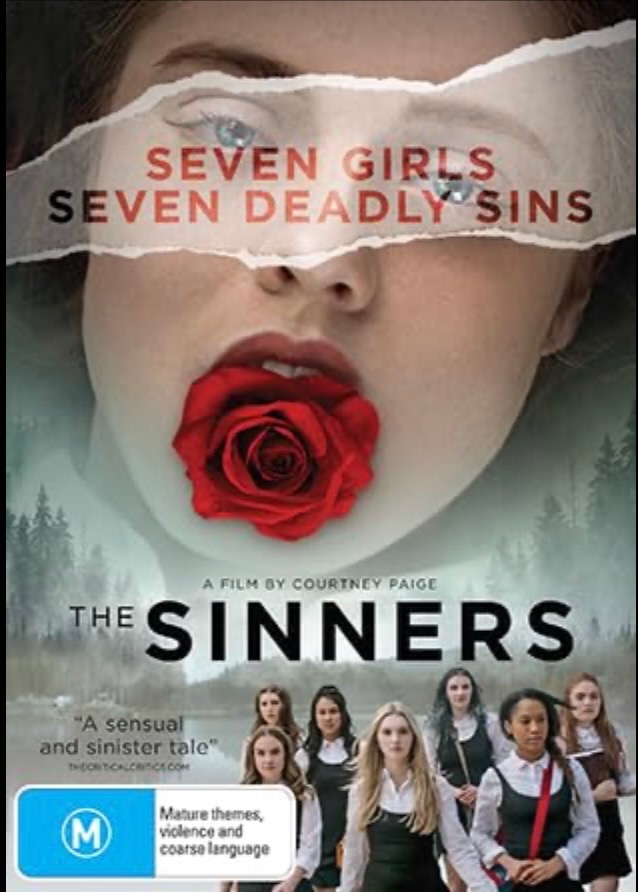

The driving force behind Holy Horror is the fact that the Bible appears in lots of horror movies. More than might be expected. Although I’ve moved on to other projects, I still keep an eye out. There may not be time or opportunity in my life to write a sequel, but you can’t unnotice the Bible in The Sinners. The title drew me in, as did its free status on Amazon Prime. It’s a Bible-based flick, for sure, but even the basic description gets religion wrong. I generally like movies by female directors, and this one was a project of Courtney Paige whose name, for some reason, sounds strangely familiar. In any case, one of the biggest blunders movies like this make is that the religion doesn’t hang together. Of course, it doesn’t say what variety of Christianity it is, but it’s of the literalist stripe.

Seven alpha females at a Christian school in a Christian community form a clique in which they’re each characterized by one of the seven deadly sins. They’re lead by the pastor’s daughter, of course. One of the girls keeps a journal in which she confides that she confessed their activities to the pastor. The betrayed girls decide to scare the offender but she escapes when they’re intimidating her. She’s found dead but then the other sinners start being murdered. The police aren’t really effective and the girls try to figure out who’s behind this. I won’t say who but I will say that it doesn’t really make much sense. Scenes jump around and characters appear with little or no introduction—it’s disorienting. But that religion…

I know enough PKs (preacher’s kids) to know they often aren’t as innocent as dad thinks (and it’s generally dad). I also know that forced conformity of religion builds resentment and resistance. But there’s something wrong here. The pastor drinks wine. Even the truly religious girls drop f-bombs. One even attends a Satanist meeting with no explanation. The pastor’s wife is having an affair. The school librarian has sex with her husband at the school between classes. They can all quote scripture, and often do. What religion is this? I couldn’t really engage with the movie because there were too many distracting religious gaffs. Hey, I don’t mind when movies show the problems with religions—they’re fair game for commentary, after all. But if you’re going to do it, try to understand the mindset of the religion you’re criticizing. There’s a lot to think about in this movie, and it really isn’t that bad. But for those who know religion there’ll be some question of which it is that’s under fire. If I ever get back to Holy Horror I’ll say more.