Feeling inferior is common among religionists. When cultures list their brightest and best, scientists often top the list and those who specialize in religion are nowhere to be found. This situation gives the lie to the fact that many scientists think about, and are influenced by, religion. That became clear to me in reading Stefan Klein’s We Are All Stardust. Not Klein’s best-known book, this is a collection of interviews with well-known scientists, unplugged. There are many big names in here, such as Richard Dawkins and Jane Goodall, as well as some less familiar on a household level. Klein, himself a Ph.D.-holder in physics, asks them somewhat unconventional questions, with the goal of bringing a more human face to scientists.

Feeling inferior is common among religionists. When cultures list their brightest and best, scientists often top the list and those who specialize in religion are nowhere to be found. This situation gives the lie to the fact that many scientists think about, and are influenced by, religion. That became clear to me in reading Stefan Klein’s We Are All Stardust. Not Klein’s best-known book, this is a collection of interviews with well-known scientists, unplugged. There are many big names in here, such as Richard Dawkins and Jane Goodall, as well as some less familiar on a household level. Klein, himself a Ph.D.-holder in physics, asks them somewhat unconventional questions, with the goal of bringing a more human face to scientists.

When asked directly, scientists admit to thinking quite a bit about religion. Of those interviewed, several are hostile to it while others accept some tenets of one faith system or another. Most of them indicate that either religion or morality plays an important role in society, if not in science itself. The sad part is almost none of them seem to realize that the study of religion can be (and among the university-trained, generally is) scientific. In academia, religious studies is often vaguely tossed in with the humanities, while others would suggest it fits under social sciences—as a sub-discipline of anthropology, for example. Few understand the field, in part because many specialists enter it for initially religious reasons, somehow tainting it.

While I enjoyed the book quite a lot—it was a quick read with plenty of profound ideas—it also had a disturbing undercurrent. The explanation that many of the interviewees gave for why they went into science was “curiosity.” The implication was that those who can’t stop asking questions, and have intelligence, go into science. Again, this feature is true of most academic fields, if they’re understood. Greatly tempted to go into science myself, I simply didn’t have the mathematical faculties to do it. While I took advanced math in high school I wouldn’t have gotten through without my younger brother explaining everything to me. My real concerns lay along the line of ultimates. Learning about Hell at a young age, it made the most sense to me—very curious and scientifically inclined—to avoid going there. To do so, the proper target of my science should be religion. While many scientists in We Are All Stardust are friendly to philosophy, religion is considered a far less worthy subject by not a few. True, religion often behaves badly in public. It doesn’t bring the money into universities that megachurches reap. But unplugged even scientists still think about it.

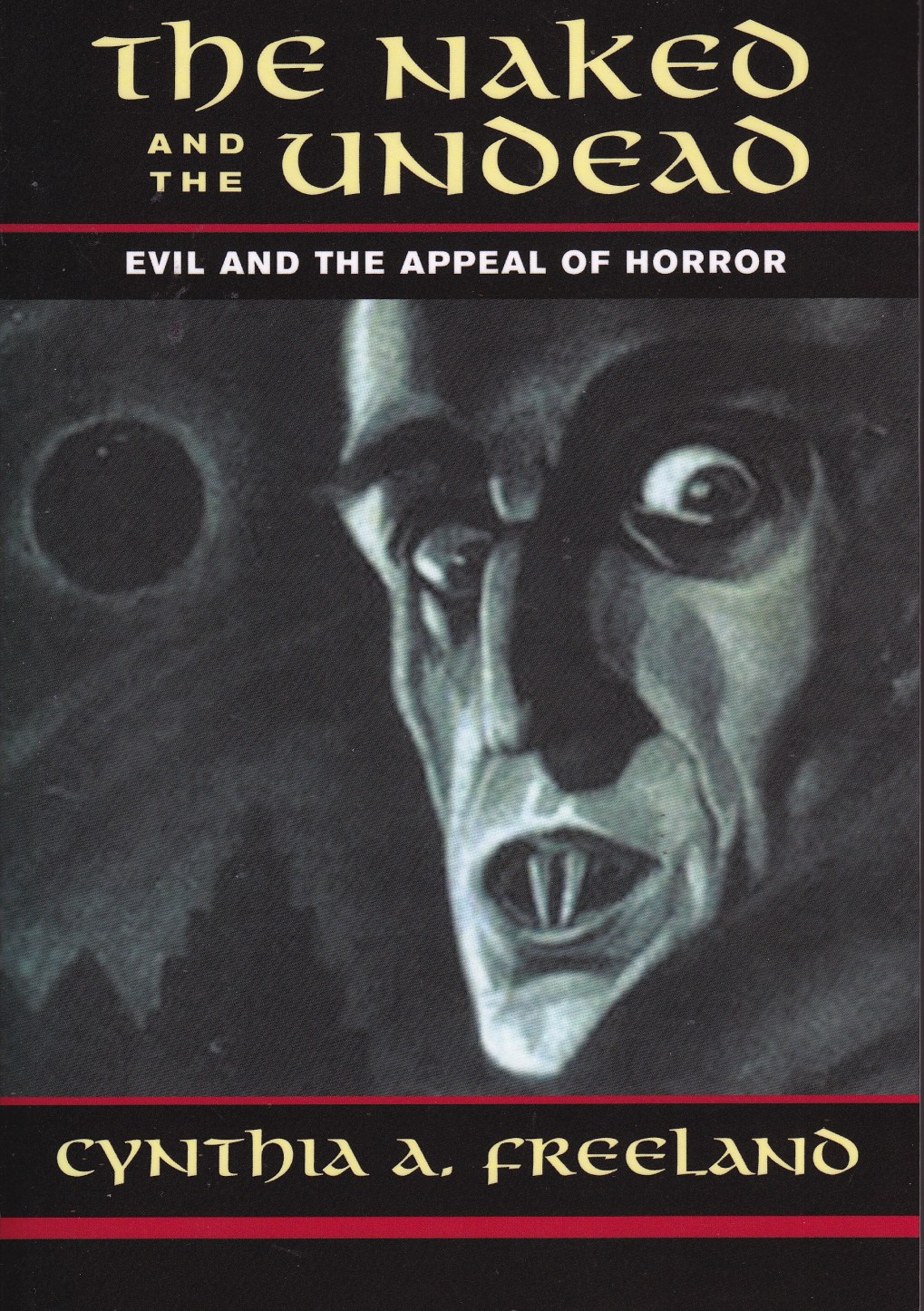

Good and evil. Well, mostly evil, actually. No, I’m not talking about Washington, DC, but about horror movies. Cynthia A. Freeland’s The Naked and the Undead: Evil and the Appeal of Horror is a study that brings a cognitivist approach to the dual themes of feminism and how horror presents evil. It’s not as simple as it sounds. Like many philosophers Freeland is aware that topics are seldom as straightforward as they appear. Feminists have approached horror films before, and other analysts have addressed the aspects of evil that the genre presents, but bringing them together into one place casts light on the subject from different angles. Freeland begins this process by dividing her material into three main sections: mad scientists and monstrous mothers (which allows for the Frankenstein angle), from vampires to slashers, and sublime spectacles of disaster. Already the reader can tell she’s a real fan.

Good and evil. Well, mostly evil, actually. No, I’m not talking about Washington, DC, but about horror movies. Cynthia A. Freeland’s The Naked and the Undead: Evil and the Appeal of Horror is a study that brings a cognitivist approach to the dual themes of feminism and how horror presents evil. It’s not as simple as it sounds. Like many philosophers Freeland is aware that topics are seldom as straightforward as they appear. Feminists have approached horror films before, and other analysts have addressed the aspects of evil that the genre presents, but bringing them together into one place casts light on the subject from different angles. Freeland begins this process by dividing her material into three main sections: mad scientists and monstrous mothers (which allows for the Frankenstein angle), from vampires to slashers, and sublime spectacles of disaster. Already the reader can tell she’s a real fan.