I just read an interesting article about how social media, and the internet in general, hijacks our time. If you’re reading this, no doubt you’ll agree. Those of us who write books on our “free time” know that the way books are both found and sold is on the web. Publishers encourage authors to build a social media platform, usually involving Twitter. Academics are often hopeless at social media—they’re lousy at following back on Twitter, as I know from experience. There is a kind of self-importance that comes with higher education which makes many of the professorate assume the work of others is less important than their own. It’s more blessed to be tweeted than to tweet others. After all, such-and-such university has hired you, and that proves the value of what you have to say.

Book publishers, however, will be looking at how many followers you have. Not that all of them will buy your book, but at least a number of them will know about it. Curiosity, indeed, drives some sales. Just like many academics, I’m jealous of my time. I’m also conscious of that of others. These blog posts seldom reach over 500 words. I tweet only a couple times a day, although I understand that’s not the way to get more followers. You need to tweet like a bird, often with images or memes, but try explaining that to your boss when each tweet is time-stamped. The academic is uniquely privileged to be given control of their time outside of class and committee meeting. Tweet away. That doesn’t mean they’ll follow you back.

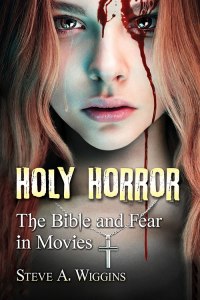

The reason for tweeting is, of course, self-promotion. 45 may understand little, but he understands that. You can commit treason and people will overlook it if you tweet persistently enough. My own Twitter activity is like the eponymous birds after which the site is named; it is active before most people are awake. And it, like this blog, is not designed to take up your time. Since my tweeting during the work day is limited, my tweets are seldom picked up. I try following other academics, but often they don’t follow back. After all, what does a mere editor have to say that could possibly be of interest to the high minded? Alas, I fear my advanced studies of the Bible have become bird-feed. And my forthcoming book won’t get noticed. I only wish more colleagues would consider the adage, tweet others as you would like to be tweeted.