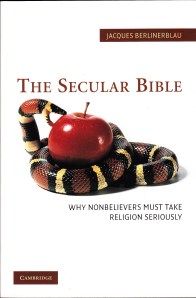

Although the academic field of biblical studies is slowly dying—this is something I wrote about a long while back on this blog—the Bible and its kin nevertheless continue to shape and control society. I was recently reading that Islam takes quite a different view of the Qur’an than Christianity does of the Bible. It’s also clear that Judaism has yet another way of looking at Scripture. What underlies these Abrahamic faiths is, however, the idea of sacred texts. They don’t have to be understood, let alone read, in order to alter perceptions of reality. The idea that God wrote a book, combined with the idea that God doesn’t show Godself or intervene in the world for good in any obvious way, has transferred a kind of godhood onto sacred scripture.

People desire the second coming because of a deep-seated need for God to part the clouds and demonstrate that their way of looking at things is the correct way. It may be influenced by Scripture or politics or a favorite news channel, but the result is the same—they want divine intervention and since it’s not forthcoming, their sacred texts become the rallying point around which they gather. Like many people I’m puzzled how a man like Trump, known for his proud womanizing and lack of care for anyone other than himself, came to be seen as a messiah. Perhaps the key is that moment he gassed American citizens for a photo op holding up a Bible he never reads. How this comes to be interpreted as a kind of divine moment only makes sense when we realize it’s the idea of Scripture that becomes the reality of many.

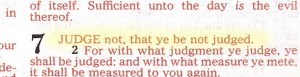

I’ve read through the Bible many times. I have to confess that trying to get through the Qur’an is a struggle for me, but I suspect quite a lot of that is cultural. I’ve read a few other sacred texts over the years, and have found some wisdom in all of them. It’s when they become divinities in their own rights that society begins to pay the price. If a non-interventionist God remains invisible, that identity will be transferred to the divine surrogate—Scripture. People will coalesce around the idol they can see rather than the invisible one they can’t, right Elijah? These sacred books have survived partially because they contain old wisdom, and old wisdom is often better than new knowledge. But they also survive because they have become, in some sense, gods.