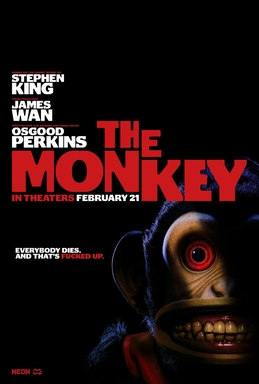

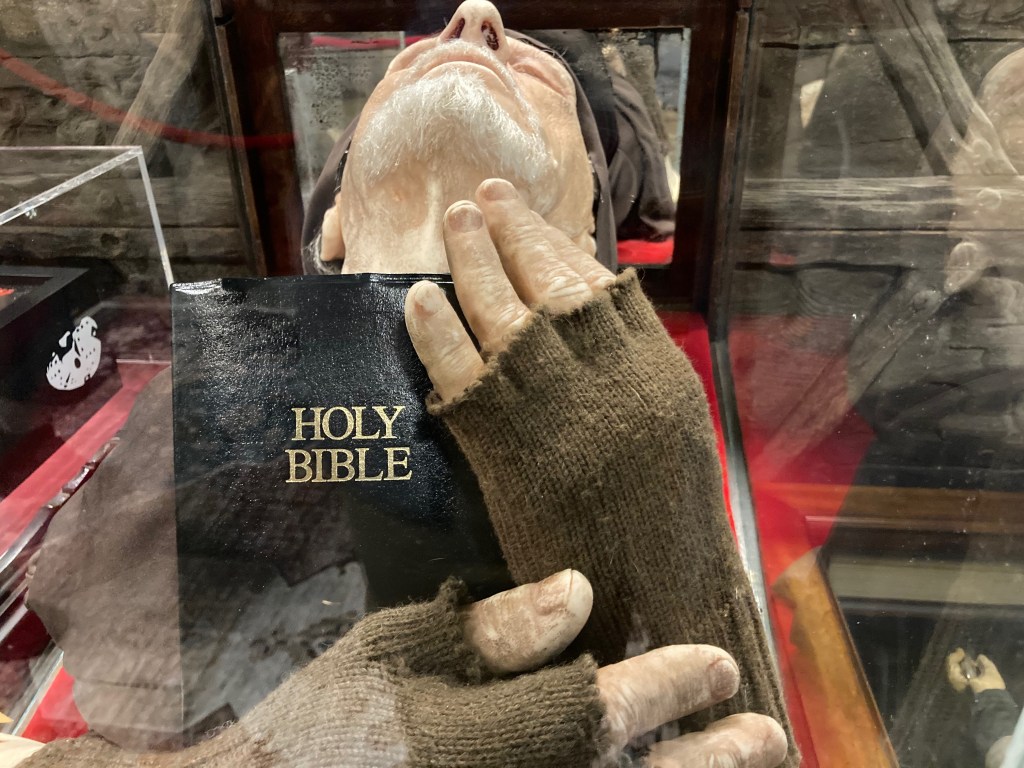

While religion isn’t a major part of the story, it appears enough in The Monkey to be noted. The movie presents probably the most inarticulate priest in cinema, played for laughs. But then again, there is quite a lot of comedy in among the gore. It’s difficult to say if the movie would’ve succeeded had it been straight horror. Based on a Stephen King short story, the plot revolve around a toy ape, actually, a drum-playing chimp that is wound up with a key. The problem is, when the last drum-stick comes down somebody nearby dies in a bizarre way. As is the way in such stories, if the “monkey” (I’ll just give in and call it that) is destroyed, which it is from time to time, it keeps coming back. When purchased by a father for his twin sons, tragedy follows until only one is left standing. The religion comes at the funerals.

The twin sons, Hal and Bill, the main human focus of the film, hate each other. This is mainly because Bill, the firstborn, bullies Hal, driving resentment. They discover the monkey among their absentee father’s effects and when they wind it up they soon end up as orphans. When it kills their guardian uncle, they put it down a well where it stays quiet for 25 years. Bill acquires the toy as an adult and harboring resentment, believing Hal killed their mother, he sets the monkey off again in the hopes that it will kill his estranged brother. A string of bizarre deaths occur, cluing Hal in to the fact that his brother is back at it. Only one of them survives while the town lies in ruins. The deaths, although gruesome, are comedic, making them bearable.

The story is dark enough that director Osgood Perkins’ decision to make it comedic appears to have been the only way to make it palatable. Horror comedy is often difficult to pull off well. Many such films wind up being simply silly or losing any potential to be frightening. The Monkey manages to blend fun and fear effectively. It also continues the long line of horror films that animate toys of various sorts, making all kinds of commentary about childhood. Of course, this film begins with Bill and Hal’s childhood and has them learning to deal with death at an early age. At the end even Death on his pale horse has a cameo. Handled differently, it could’ve been quite terrifying. Especially since the religion in this world is so completely ineffectual.