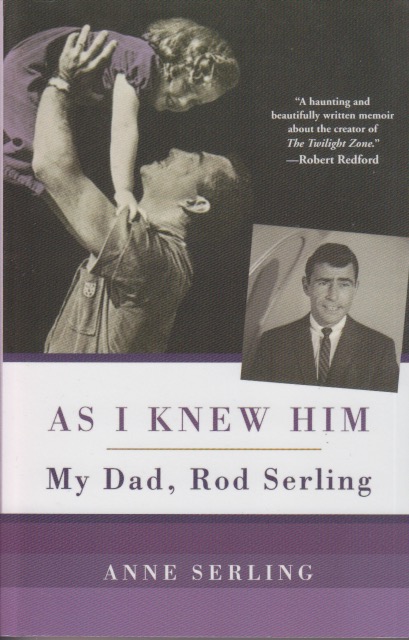

Born Jewish, and Unitarian by choice, Rod Serling believed in the inherent worth and dignity of all human beings. Like many people, even Serling believed that season four of The Twilight Zone, which went to an hour format from the usual half, didn’t really work. Nevertheless, the fourth episode of that season,“He’s Alive,” really should be required watching of every person in the United States. This episode was written by Serling and it focuses on a young American fascist who’s having trouble gaining a following. A shadowy figure then reads to him from what sounds exactly like Trump’s playbook, and soon decent people are raging along with him about foreigners and those who are different. When the shadowy figure is finally revealed, we’re not surprised to learn it is Hitler.

The young man obeys without question, and soon it looks like he could be elected. He has one of his best friends killed as a martyr to the cause. He murders an old Jewish man who has cared for him since his youth. He declares himself made of steel, with no feelings. And when he ends up dead (everyone knows how Hitler’s career culminated), the spirit of Hitler rises from his body as Serling warns that wherever hatred exists, Hitler still lives. Now this episode aired in 1963 but it could’ve been 2016, or 2024. Prescient people, like Rod Serling, knew that mob thinking could be easily exploited. Even in the first segment after the introduction the instructions are laid out. Play on people’s fear of those who are different. No matter how good things may be, people will be unsatisfied. Add any power-hungry individual and you’ve got the recipe for a fascist overtaking.

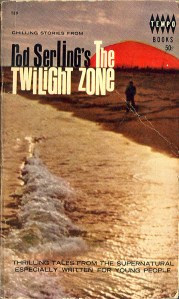

The episode made me wonder if we could ever become a just society. Ironically, that which calls itself “Christianity” these days stands in the way. In its day, The Twilight Zone was amazingly influential. It had a great impact on what was to follow and it’s still regularly referred to, even by those who’ve never seen an episode. If only we’d pay attention to its message. I’ve been making my way through the entire series, slowly, over the years. Now and again an episode will really hit home. I have to admit that I was physically squirming during “He’s Alive.” It’s not that it is the greatest episode of the series, but its message is extremely timely. The requirement for a better world is simple, but seemingly impossible to reach. Treat others as you wish to be treated.