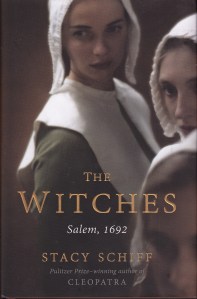

Witch-hunts, I suspect, will become all the rage again if a certain presidential candidate is elected. The fear of witches is not easily explained in a world driven by materialism, but certainly misogyny plays an unholy role in much of it. Stacy Schiff’s The Witches: Salem, 1692 has been selling well. Since my wife is one of the many descendants of the Towne family that suffered three witch accusations resulting in two executions (Rebecca Nurse, Mary Esty, and Sarah Cloyce) we read this book together. It is a detailed account of the year we went mad. A year when being different, especially not being Puritan, and not being male, was dangerous. Religious tolerance was not a gleam in the colonists’ eyes since religious freedom translated into not being forced into the government church, not allowing others the same privilege. Indeed, as Schiff points out, religious tolerance was considered by many to be a satanic idea. If ministers starved due to such freedom, it would be easy for Satan to take over. As it was, the Dark Prince seems to have done a pretty good job among the Puritans without such tolerance.

Witch-hunts, I suspect, will become all the rage again if a certain presidential candidate is elected. The fear of witches is not easily explained in a world driven by materialism, but certainly misogyny plays an unholy role in much of it. Stacy Schiff’s The Witches: Salem, 1692 has been selling well. Since my wife is one of the many descendants of the Towne family that suffered three witch accusations resulting in two executions (Rebecca Nurse, Mary Esty, and Sarah Cloyce) we read this book together. It is a detailed account of the year we went mad. A year when being different, especially not being Puritan, and not being male, was dangerous. Religious tolerance was not a gleam in the colonists’ eyes since religious freedom translated into not being forced into the government church, not allowing others the same privilege. Indeed, as Schiff points out, religious tolerance was considered by many to be a satanic idea. If ministers starved due to such freedom, it would be easy for Satan to take over. As it was, the Dark Prince seems to have done a pretty good job among the Puritans without such tolerance.

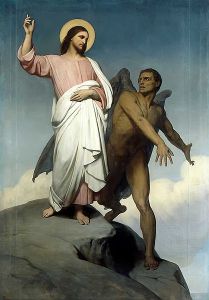

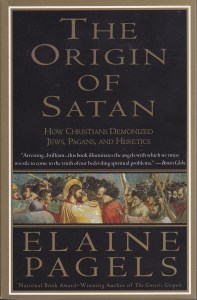

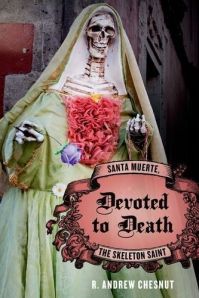

The idea of the Devil has been (and still is) the ultimate scapegoat. People in a capitalist society are naturally frustrated—surprisingly few see this—and frustration always seeks a reason for its own existence. That is patently clear at Salem: blame the Indians, blame the French, blame the Quakers, blame the women. Any and all may be agents of the Devil. Even the descriptions of the Lord of Darkness varied so much that, were he a human, no one could be quite sure who it was they saw. The Devil always takes the form of your enemy. All it takes is an influential clergy willing to push tense believers over the edge. Soon we begin building walls. Then we build gallows.

Religious tolerance has always been a frightening thought. Protestantism challenged a somewhat uniform Catholicism and the mite of a doubt burrowed deeply into peoples minds: is my religion the wrong one? Tolerating other religions means admitting that yours might be wrong. The logic that plays itself out is a terrifying one to some. Belief is never easily changed. States can’t stand dissenters. The only capital crime for which the federal government still executes citizens is treason. Treason sits uncomfortably on the other side of the coin whose obverse reads “tolerance.” You’d think that three centuries would be long enough to learn something. Unfortunately some lessons—often tragic ones for the powerless—have to be played out over and over before we start to comprehend that Satan can be anyone we want him to be.