Few topics have to be approached as gently as space aliens. Those who’ve seen UFOs are subject to an immediate ridicule response partly generated by the belief that galactic neighbors, if any, are simply too far away to get here. So when the Washington Post runs not one, but two stories in the same week about the subject of UFOs, without a hint of snark, it’s newsworthy. I’m in no position to analyze the journalistic findings, but I do consider the idea that other species might be more advanced than we are not at all unlikely. Look at what’s going on in Washington DC and dare to differ about that. Human beings, now that we’ve rid ourselves of deities, have the tendency to think we’re the hottest stuff in the universe.

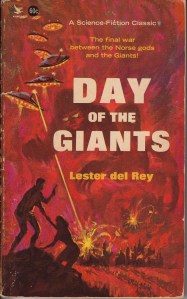

I’ve admitted to being a childhood fan of science fiction. Space stories were always among my favorites in that genre. When I learned in physics class that travel faster than the speed of light was impossible, I was sorely disappointed. I also learned about the posited particles known as tachyons that do travel at such speeds. This to me seemed a contradiction. Or at least short-sighted. If our primitive physics suggests that some things can travel faster than light, why limit our ET visitors to our technological limitations? This wasn’t naivety, it seemed to me, but an honest admission that we Homo sapiens don’t know as much as we think we do. The universe, I’m told, is very, very old. Our species has been on this planet for less than half-a-million years. And we only discovered the windshield wiper in 1903.

Around about the holiday season people’s thoughts turn to heavenly visitors. What would the Christmas story be without angels? (For the record, some evangelical groups have historically claimed UFOs were indeed angels, while others have called them demons.) The idea was championed by Erich von Däniken, if I recall correctly from my childhood reading. Where angels might come from in a post-Copernican universe is a bit of a mystery. As is how they’d fly. Those wings aren’t enough to bear a hominid frame aloft, otherwise we’d see flying folks everywhere, without a two-hour wait at the airport. Then again, belief in angels almost certainly will lead to ridicule among the cognoscente of physicalism. The presents have been unwrapped, and angels have been forgotten for another year. And who could know better what’s possible in this infinite yet expanding universe than “man the wise,” Homo sapiens?