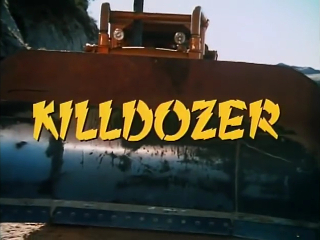

Funny how some things just stick in your mind. And then come back at odd times. Killdozer was a television movie from 1974. I must’ve watched it pretty close to when it first aired. Why it came back to me half a century later I just don’t know. I haven’t been around any heavy earth-moving equipment lately, nor have inanimate objects been threatening me. When I found it on a free (albeit with commercials, but hey, the original had commercials, so it’s a full circle kind of phenomenon) streaming service, I figured why not? I was really expecting something cheesy, like I would’ve liked at eleven or so. It wasn’t really that bad. There’s actual characterization and the acting is believable. Only the special effects of the meteorite and the blue glow were obviously low budget. But you might not be familiar with the D9, so let’s go.

An uninhabited island off the coast of Africa. Six guys on a construction job—building an airstrip for a petroleum company. The supply ship’s a few days away and when the Caterpillar D9 hits the meteorite, it becomes a murderous machine, like Stephen King’s Christine. You can outrun a bulldozer, for a while, anyway. But if it never runs out of fuel, and you’re trapped on an island, your chances aren’t good. They’re even worse if the thing is sentient and knows what you’re planning to do. Six men were sent to the island, and only two make it back. You get the picture.

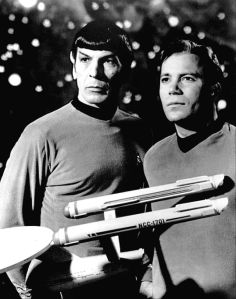

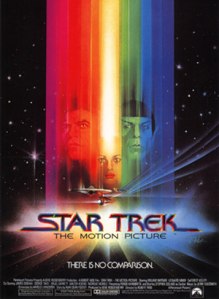

As a child I had no idea who Theodore Sturgeon was. When I saw that this was based on one of his stories, I had to ponder a bit. Sturgeon wrote several of the original Star Trek series episodes. His most famous stand-alone story seems to be Killdozer. In fact, it’s become a cult classic. I don’t have many friends, so I’m not always aware of what’s in during any given decade. I think kids at school were talking about Killdozer, but nobody has really uttered that word in my hearing since Gerald Ford was president. So if you don’t mind commercials, and you have a sleepy spare hour, some of us would be interested to hear what you think about this movie. The sense of isolation and people being killed by something they construct to be basically indestructible struck me as a lesson worth pondering. And I’ll continue to try avoiding heavy earth-moving equipment, just in case.