It’s important to keep the old gods happy. By now everyone probably knows that Stephen King composed a tweet suggesting that Donald Trump was Cthulhu. In response an angry tweet came from Cthulhu himself, since, as we know, he declared his intention to take over the world long before Trump. Cthulhu is no stranger to this blog, being the brainchild of H. P. Lovecraft. As I’ve suggested before, however, it is really the internet that gave life to the ancient one. His name is instantly recognizable to thousands, perhaps millions, who’ve never read Lovecraft or his disciples. In parody or in seriousness, the worship of Cthulhu is here to stay.

I’ve often wondered if the internet might participate in the birth of New Religious Movements. In an era when a completely unqualified plutocrat can run for president just because he has other people’s cash to burn, anything must be possible. Cthulhu, as we all know, lies dead but dreaming beneath the sea. His coming means doom for humankind, or, at the very least insanity. It seems that Stephen King might be right on this one. I’m getting old enough to recognize the signs; after all John F. Kennedy was president when I was born. I’ve seen the most powerful office in the world devolve into a dog-and-pony show where lack of any guiding principle besides accrual of personal wealth can lead a guy to the White House. At Cthulhu’s tweet indicates, reported on the Huffington Post, at least he’s honest. Unlike some political candidates, many people believe in Cthulhu.

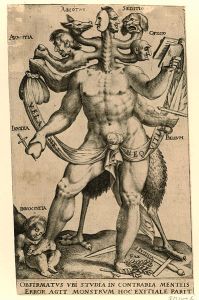

Perhaps the interest in Cthulhu is just a sophisticated joke. Long ago I suggested to a friend of mine in Edinburgh that perhaps the Ugaritians were writing funny stories (i.e., jokes) on their clay tablets, imagining what future generations would say when the myths were uncovered. Like Cthulhu, they were the old gods too. Like Cthulhu, there are people today who’ve reinstituted the cult of Baal and the other deities that would’ve led to a good, old-fashioned stoning back in biblical days. New Religious Movements are a sign that we’re still grasping for something. Our less tame, or perhaps too tame, deity who watches passively while charlatans and mountebanks dole out lucre for power must be dreaming as well. Of course, Lovecraft, the creator of Cthulhu, was famously an atheist. Belief is, after all, what one makes it out to be. At least Stephen King’s father reinvented his surname with some transparency. And those who make up gods may have the last laugh when the votes are all in.