I couldn’t have been an easy kid to raise. As a teen, while other kids were experimenting with drugs and sex, I started an unexpected habit. I can’t remember why or how it happened. I was the son of a professional drunk and a high school dropout. (Step dad worked in a sewage plant, so that likely wasn’t it either.) Somehow I’d discovered classical music. It wasn’t through records we had at home. If the artist didn’t have Cash or Twitty in their name you were probably tuned into the wrong station, buddy. Since this was before the internet it must’ve been something I heard on television. On Saturdays I’d beg to go to the Oil City Public Library where you could borrow LPs. I’d check out five at a time, and listen to them with headphones on at home. The general opinion in my neighborhood was that this was snob music and other people didn’t want to hear it.

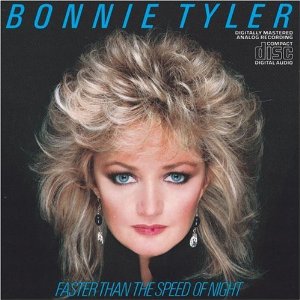

One of the pieces I discovered was Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, (officially The Year 1812). This particular recording began with a chorus singing the Russian hymn, in English (hey, I was just learning!). Although I loved the bombastic ending (what boy wouldn’t?) I was haunted by that hymn. I paid no attention to the conductor—I couldn’t tell a Stravinsky from a Stokowski—so I memorized the albums I liked by their cover art. As a teen I had no idea things would ever change and that one day I’d be downloading music instead of carefully, lovingly pulling it out of a colorful sleeve, breathing in the experience.

Russia’s been on a lot of people’s minds lately. I have a great deal of respect for the Russian people. There’s a stolidity and pathos there that is rarely captured in any national music. I longed to hear that recording again. It took the better part of a day searching the internet to find it—I could walk right up to it in the Oil City Public Library four decades ago and put my hand on it. Those days are gone. When I finally located it on YouTube (Eugene Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra, in case you’re interested) I couldn’t stop listening. Not only did it take me back to my fractured childhood, it also made me feel a deep connection for a nation that probably looks at my own with great and earned distrust. We all need to learn to look at ourselves from the outside. That hymn! Listen to the words. I could imagine myself being oppressed by people I didn’t know and who had no reason to hate me. Unto our land bring peace. Amen.