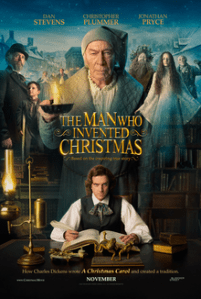

Breaks are good for many things. Time with family and friends. Hours of non-bus time for reading. Watching movies. So it was that we went to see The Man Who Invented Christmas. It really is a bit early for my taste, to think about Christmas, but the movie was quite welcome. Being a writer—I wouldn’t dare to call myself an author—one of my favorite things to do is talk about writing. Watching a movie about it, I learned, works well also. The conceit of the characters following Dickens around, and refusing to do what he wants them to should be familiar to anyone who’s tried their hand at fiction. My experience of writing is often that of being a receiver of signals. It is a transcendent exercise.

Not only that, but in this era of government hatred of all things creative and intellectual, it is wonderful to see a film about writing and books. The reminder about the importance of literacy and thought is one we constantly have to push. If we let it slip, as we’ve discovered, it may well take considerable time to recover. Getting lost in my fiction is one of my favorite avocations. Solutions to intractable problems come at most improbable times. Although publishers tend to disagree with me, I find the stories compelling. In the end, I suppose, that’s what really matters.

On an unrelated note, this is the second movie I’ve seen recently that attributes non-human actors their real names in the cast listing. What a welcome break from the blatant speciesism that pervades life! Animals have personalities and identities. Humans have often considered the privilege of being named to be theirs alone. True, animals can’t read and wouldn’t comprehend a human art form such as cinema. But when they communicate with each other, they may well have names for us. The beauty of a story such as A Christmas Carol is that it reminds of the importance of generosity. We should be generous to those who take advantage of our kindness. Our time. Our energy. We should also be generous to those who aren’t human but are nevertheless important parts of our lives. The movie may have come too early for my liking, but the holiday spirit should never be out of season. If we’ve made a world that only appreciates kindness because much of the rest of the year is misery, it means we’ve gone too far. Films can be learning experiences too, no matter the time of year.