Water is essential for life. Life as we know it, in any case. It is no surprise, then, that many religions incorporate water into their rituals. Last week I posted about the biblical stories of Jonah and Noah, both of which involve acts that were later interpreted by Christians as baptism. Muslims use ritual ablutions as part of their worship tradition. Water is life, after all.

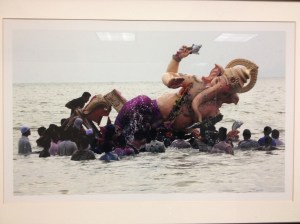

While wandering the halls at work, I notice the various artwork on the walls. One large, framed image has frequently caught my attention: several men are shown carrying a statue of Genesha, the Hindu elephant-headed god, through the water. Coming at this from a Christian background, I wondered what was going on since it looks like baptism. Hinduism, I know, is not a unified religion, but rather a conglomeration of many folk traditions from ancient India—one of the two seats of ancient religiosity. The stories of ancient India are colorful and diverse, and a bit of research suggests that this particular photo is likely the festival Ganesha Chaturthi, commemorating the story of how Ganesha came to have an elephant’s head. Crafted from inert matter by his mother Parvati, Ganesha was posted to watch the door while his mother bathed. Parvati’s consort Shiva returned and not knowing who the boy was, the lad’s refusal to allow anyone to enter led to a war. Eventually the Ganesha was beheaded and to appease his consort, Shiva supplied him with the head of a dead elephant and the boy resurrected. The immersion of Ganesha statues, or Visarjan, takes place as part of the Ganesha Chaturthi, during August or September.

I admit I’m not an expert on Hinduism, so some of the details may be a little off here. What strikes me, however, is the similarity between this story and that of Jesus. Like Ganesha, Jesus was associated with a modest mother, slain, and resurrected. He, too, is associated with ritual baptism. Growing up, we were taught of the many unique aspects of Christianity. We had, we were led to believe, the only resurrecting deity in the world. Our God alone could bring back from the dead, and the way in was through immersion in water. While learning about Ugaritic religion I read of Baal’s death and resurrection. Although stories of baptism haven’t survived, he also battled the sea and came out victorious. Some ideas, it seems, are particularly fit for religious reflection. The details may be unique, but the archetypes are very similar. Religions may be many things, but in the end, unique is a word that must be applied with the greatest of care. In the meanwhile, the next time I read of walking on the water, I will recall that even Asherah was know as “she who treads upon the sea.”