One of the most compelling characters of the Bible is John the Baptist. Unconventional and non-conformist, he speaks with unquestioned authority based on pure conviction. Baptism comes in many forms. When we moved our daughter into her dorm room, we found water from the HVAC vent dripping on her bed. I’ve been similarly baptized on NJ Transit buses in the summer when the condensation gathers just above my head. (Of course, being on the bus, I’m always hoping that it’s only water.) Considering how well HVAC contractors seem to be paid, it is always a wonder to me that little things like leaks can’t be sought and settled. Water always seeks the lowest point. In baptism a person is plunged even lower, beneath the water. It’s kind of like drowning.

I was baptized in a river (or a creek that passed for a river in my part of Pennsylvania). Our church didn’t believe in infant baptism, so I was old enough to know that I was to be held under the surface for a second or two—a frightening prospect for a non-swimmer like me. It turned out alright, as these things generally do, and my ten-year-old sins were washed away to be somebody else’s problem further down stream.

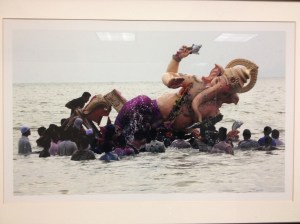

The origins of baptism are somewhat of a mystery. Many religions include purification rituals, including Judaism. Judaism, however, never seems to have taken ritual washing to the level demanded of John the Baptist. Even he had a rather tepid view compared to that of later Christians who made salvation without it impossible. It is perhaps the implicit admission of shame, or possibly the public spectacle of it all that makes it such a rite. Being rained on in the presence of a priest doesn’t count. Nor does, in some traditions, a mere trickle on the head. The victim must be cut off from the air above. Religion does insist on a fair bit of threat for believers as well as non. And so the water drips. Of course it’s a holiday weekend so they can’t get the maintenance guy to fix it until at least Tuesday. As we wait we know that the water will always continue to seek the lowest point.