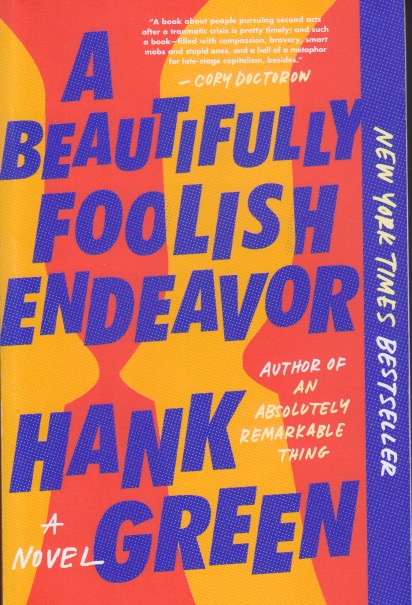

By their very nature they make us wonder what they’re up to. Secret societies, I mean. That’s part of their appeal. Those on the outside speculate and usually the ideas swirl around mysterious rights and probably sex and money. Leigh Bardugo takes it in a different direction in Ninth House. Since I try not to read reviews before getting into a book, I wasn’t aware of the premise that the secret societies of Yale University were the nine houses referred to in the title. Bardugo’s imagination takes the route of suggesting that they all specialize in different kinds of magic. That makes this kind of a fantasy horror novel because the protagonist, Galaxy Stern (“stern” is, of course, German for “star”), can see ghosts. And some of the professors aren’t who you think they are.

Somewhat gritty, Alex (Galaxy) isn’t exactly college material, let alone Yale. She’s a recovering drug runner who has a past that would keep her out of most universities, particularly those of the Ivy League. Still, she’s invited to Yale and she has some personal motivations, not necessarily academic, to accept. She’s brought there by the ninth house, Lethe, because of her ability to see ghosts. As portrayed in the novel Lethe is the secret society that makes sure the others don’t go beyond their bounds, the police, if you will. Each society specializes in a specific kind of magic and it uses it to help its members benefit in school and career. That’s why the university is so well funded. It paints a compelling image of New Haven and it manages to capture the mystery many of us felt about attending college in the first place.

Yale is one of the two Ivy League campuses I’ve never been on (the other is Dartmouth). Even so, Bardugo writes in a way that makes you feel as if you’ve been there. The story is a page-turner that goes quickly for its size. Alex, who is a novice in Lethe, spends the novel trying to find her mentor, Darlington, who’s been missing since some bad magic got him. There are many unexpected twists along the way. Although I don’t know much about Bardugo’s past, it seems likely that she knows some people in the drug culture. Maybe she’s even seen some ghosts. All of this combines to make a magical read that should appeal to Neil Gaiman fans as well as those of Stephen King. And, of course, those who like to speculate about secret societies.