Stretching back before the advent of writing, back before civilization itself began, people have shown reverence for their dead. Paleolithic era grave goods attest to care of the dead residing among the earliest strata of human behavior, and it is a behavior that continues to evolve to reflect the belief structures of the Zeitgeist. The idea of constructing cemeteries in a garden where family and friends might visit their departed is a relatively recent innovation. Increased population and concerns about epidemics led to the landscaped, garden-variety cemetery outside of populated areas in the 18th century. Before that graveyards could be located within the city itself, often near a church or sacred location.

While visiting Swan Point Cemetery in Providence, my niece asked me why people left pennies on gravestones (H. P. Lovecraft’s tombstone had one on it, and others around it). My thoughts went to Wulfila’s recent blog post on the Black Angel tomb in Iowa City and the pennies scattered there. I also recalled La Belle Cemetery in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin where a “haunted statue” was always richly endowed with pennies in her cupped hands.  The specific form of penny offerings seems to go back to Benjamin Franklin’s burial, at least in America. A few years back while in Philadelphia, I saw for myself that people still leave pennies on Franklin’s grave in Christ Church Cemetery.

The specific form of penny offerings seems to go back to Benjamin Franklin’s burial, at least in America. A few years back while in Philadelphia, I saw for myself that people still leave pennies on Franklin’s grave in Christ Church Cemetery.

Franklin pennies (and a few nickles)

There is no universally accepted reason explaining why Benjamin Franklin should have been the first to have received such treatment — in fact, I would argue that it is much older than Dr. Ben.

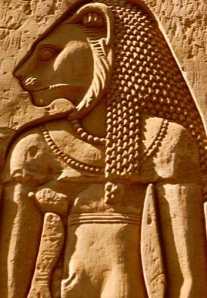

Money to accompany the dead has a long history. Pennies on the eyes or under the tongue of the deceased originated in the need to placate the ferryman across the river of — what’s it called? — Oh, yes, the river of forgetfulness. The classical Greek form of this mythic character is Charon, the boatman who punted the dead across Styx. He required payment, and since coinage had been invented, it was a convenient way to pay. (Today the truly devoted might leave a credit card in the casket.) The ferryman must have his pay, as the movie

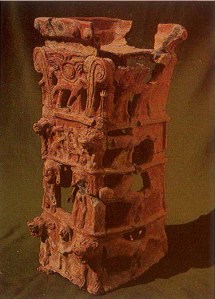

Ghostship warns, but the idea is much older still. The earliest references to being poled across the river go back to ancient Sumer, the earliest known civilization. As soon as people became civilized they began to pay homage to the gloomy captain of souls.

While in Prague just after it opened to western visitors, my wife and I stopped by the famous Jewish cemetery where the tombstones are so tightly packed in that they are barely legible. My wife asked why so many of the tombstones had smaller stones on top, placed there as dedications. I recalled having seen stones on tombs outside Jerusalem some years back, and I even had a student bring me a stone from Israel to keep as long as I promised to put it on her grave after she died. This practice in its recent form is associated with Judaism, but again, it has ancient roots. The building of cairns, or piles of stones, is often associated with the Celts or the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the British Isles. On our many wandering through the highlands and islands we saw several Neolithic examples in Scotland, particularly in the Orkney Islands. The practice of putting stones atop the dead also goes back to ancient times. One plausible suggestion is that it was intended to keep the dead in their graves. A more prosaic conclusion is that digging deep holes takes more work than hauling over a pile of rocks.

I recalled having seen stones on tombs outside Jerusalem some years back, and I even had a student bring me a stone from Israel to keep as long as I promised to put it on her grave after she died. This practice in its recent form is associated with Judaism, but again, it has ancient roots. The building of cairns, or piles of stones, is often associated with the Celts or the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the British Isles. On our many wandering through the highlands and islands we saw several Neolithic examples in Scotland, particularly in the Orkney Islands. The practice of putting stones atop the dead also goes back to ancient times. One plausible suggestion is that it was intended to keep the dead in their graves. A more prosaic conclusion is that digging deep holes takes more work than hauling over a pile of rocks.

No matter what the origin of the practice may be, one of the surest signs of civilization is care for the welfare of the dead. Today a penny is easily left, costs the bearer little, and creates a memorable image for all who follow.

The specific form of penny offerings seems to go back to Benjamin Franklin’s burial, at least in America. A few years back while in Philadelphia, I saw for myself that people still leave pennies on Franklin’s grave in Christ Church Cemetery.

The specific form of penny offerings seems to go back to Benjamin Franklin’s burial, at least in America. A few years back while in Philadelphia, I saw for myself that people still leave pennies on Franklin’s grave in Christ Church Cemetery.

I recalled having seen stones on tombs outside Jerusalem some years back, and I even had a student bring me a stone from Israel to keep as long as I promised to put it on her grave after she died. This practice in its recent form is associated with Judaism, but again, it has ancient roots. The building of cairns, or piles of stones, is often associated with the Celts or the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the British Isles. On our many wandering through the highlands and islands we saw several Neolithic examples in Scotland, particularly in the Orkney Islands. The practice of putting stones atop the dead also goes back to ancient times. One plausible suggestion is that it was intended to keep the dead in their graves. A more prosaic conclusion is that digging deep holes takes more work than hauling over a pile of rocks.

I recalled having seen stones on tombs outside Jerusalem some years back, and I even had a student bring me a stone from Israel to keep as long as I promised to put it on her grave after she died. This practice in its recent form is associated with Judaism, but again, it has ancient roots. The building of cairns, or piles of stones, is often associated with the Celts or the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the British Isles. On our many wandering through the highlands and islands we saw several Neolithic examples in Scotland, particularly in the Orkney Islands. The practice of putting stones atop the dead also goes back to ancient times. One plausible suggestion is that it was intended to keep the dead in their graves. A more prosaic conclusion is that digging deep holes takes more work than hauling over a pile of rocks.

Here is a Gnu-license photo of one of these clouds; there are more dramatic images, but they are mostly covered by copyright. What immediately caught my attention in the Wired article was the subtitle: “Weather Geeks Are Championing a New Armageddon-Worthy Cloud.” The Bible appears in the sky yet again.

Here is a Gnu-license photo of one of these clouds; there are more dramatic images, but they are mostly covered by copyright. What immediately caught my attention in the Wired article was the subtitle: “Weather Geeks Are Championing a New Armageddon-Worthy Cloud.” The Bible appears in the sky yet again.