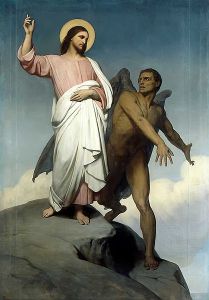

One of the most misunderstood of biblical phenomena is prophecy. One of the reasons it’s so misunderstood is that other ancient peoples came to associate it with predicting the future. Now, what prophets said often had implications for the future, but they were more forth-tellers, as they say in the biz, than fore-tellers. Amos, for instance, was a prophet concerned with social justice. We know little about his life, but we can discern that ancient prophets could be paid to become “yes men” (“yes persons” just doesn’t sound right, and most were male) for the establishment. Kings then, as now, surrounded themselves with sycophants who would tell them their policies were approved, or even ordained by God. Amos was not one of those.

Amos points out in the book attributed to him that he was no paid prophet. He was an honest worker with a great concern for social justice. He lived in a prosperous time, but the wealth disparity between the rich and the poor troubled him. (Amos has never been a favorite among prosperity gospelers, since his message has always been recognized as authentic among both Jews and Christians and he condemns the inequality rampant in society.) Many in the eighth century BCE believed ceremonial actions—like, say, holding up a Bible in front of a church—pleased God. Amos boldly declared such things sickened God as long as society favored the rich at the expense of the poor. There’s a reason Evangelicals and Republicans tend to avoid Amos. “But let judgment run down as waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream,” is not an easy thing to hear when you’re busy giving tax breaks to those who earn more than enough while refusing basic health care to the poor.

Prophets tend to speak of the future in conditional terms. If your ways don’t change, then this will happen. Some Christians, anxious to prove that Jesus was the messiah, came to see prophets as great predictors of the future. Amos would likely have taken exception to them. Even in his own day Amos made people uncomfortable. His favorite image for God was that of a lion ready to attack. His contemporaries told him to shut up. Amos then made the famous statement that he was no professional prophet. He would not adjust his message so that the comfortable could feel good about themselves. If Amos were in America the last four years would’ve had his throat raw with pointing out to “Christians” how they’d come to misrepresent everything the prophets stood for. We need more like him today.