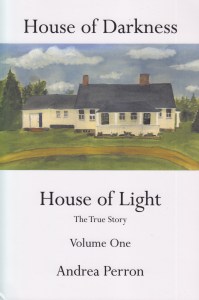

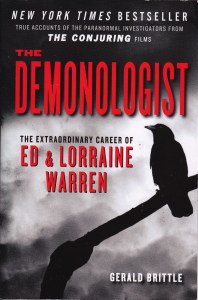

Although it may be only a venial sin, overwriting is nevertheless an offense. As a professor I read many papers from students who had great difficulty clarifying what they were thinking only to disguise it with too many words. I have finally finished Andrea Perron’s House of Darkness, House of Light. Because academics too often dismiss personal testimony, I feel compelled to consider it. Now over 1,300 pages later, I have discharged my duty. Ed and Lorraine Warren, despite being famous, are difficult to assess in book form. Yes, they (ghost-)wrote ten books, but they never had permission to include the Perron story that stands behind The Conjuring. The eldest daughter took on the task herself and even seems to be aware of (in the acknowledgements) a dubious talent for overwriting. What the Warrens saw as demons, she sees as ghosts. Who has the right to decide?

Although it may be only a venial sin, overwriting is nevertheless an offense. As a professor I read many papers from students who had great difficulty clarifying what they were thinking only to disguise it with too many words. I have finally finished Andrea Perron’s House of Darkness, House of Light. Because academics too often dismiss personal testimony, I feel compelled to consider it. Now over 1,300 pages later, I have discharged my duty. Ed and Lorraine Warren, despite being famous, are difficult to assess in book form. Yes, they (ghost-)wrote ten books, but they never had permission to include the Perron story that stands behind The Conjuring. The eldest daughter took on the task herself and even seems to be aware of (in the acknowledgements) a dubious talent for overwriting. What the Warrens saw as demons, she sees as ghosts. Who has the right to decide?

I wish the author well in her writing career—those of us who write tend to be natural boosters of others—but it would’ve been nice to have had a more condensed version focusing on the events in the Harrisville house. One interesting thing caught my attention here: according to Perron the Warrens called by phone after the Perrons moved from the offending house and tried to talk Carolyn, the mother, into a book deal. Offering a healthy income from the proposition, they gave a hint of what other writers have claimed—they had the business angle firmly in mind. I’ve read enough from people who actually knew the Warrens to believe they sincerely believed they were helping people. They also had to make a living, and ghost stories tend to sell well. Some use that as evidence that they were only trying to make money. I’d remove the only, without dismissing the financial incentive.

It’s nearly impossible to read a very long book and feel that you haven’t come to know the author. Also, it’s difficult to dismiss material written, even if overwritten, so sincerely. We live in a world that we don’t understand nearly as well as we think we do. Call it old school on my part, but I believe in extending the benefit of the doubt to eyewitnesses, particularly when there are several of them and they have a decade to observe closely what many others never get a chance to see. This set of three books is a window into a realm over which the drapes are usually drawn. For those willing to do some hard mining, there’s something of value here.