As is my custom on this last post of the year I’ll be revisiting the books that made an especial difference to me in 2016. I record most books I finish on Goodreads, and I welcome friends in that venue. I draw on their recollection for what I’ve read and all of the books I mention here have individual posts on this blog. Use the search function. It’s free!

The first important book was Scott W. Gustafson’s At the Altar of Wall Street. If you missed this one, it is well worth your time. Economics has become a religion. If you doubt that, look at 11/9 and tell me so. Philip Gulley’s The Quaker Way was also an early read that’s worth revisiting. November has made many of these books more important than they seemed at the time. Whitley Strieber and Jeffrey Kripal’s The Super Natural will expand the minds of those who allow for unconventional possibilities. And Marc Bekoff’s Minding Animals will remind us we’re not alone on this planet. The Soul of an Octopus by Sy Montgomery was a book I really couldn’t put down, and a nice complement to Bekoff. Marcelo Gleiser touched a chord with The Simple Beauty of the Unexpected, a book worthy of anyone who wants to consider how science and humanity might cooperate for everyone’s benefit. While not really a reading-through book, Tristan Gooley’s The Lost Art of Reading Nature’s Signs is important and worthy of attention.

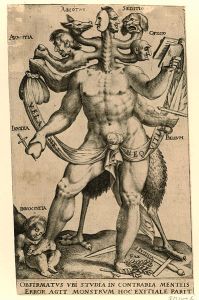

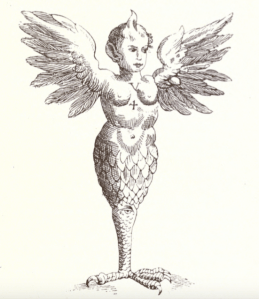

In the realm of monsters, Elizabeth Baer’s The Golem Redux was a fantastic introduction to a Jewish legend that I revisited in three more books over the year. Several other monster books followed, but especially memorable were Carol Clover’s Men, Women, and Chainsaws, and Maya Barzilai’s Golem—please be patient with me regarding this one. I haven’t written a post on it yet, since an official review has yet to be published. Alexandra Petri’s A Field Guide to Awkward Silences won her an instant fan. I’ll read anything she writes. I didn’t give Alice Miller’s The Drama of the Gifted Child the attention it deserves. It’s kind of a personal thing. Kyle Arnold’s The Divine Madness of Philip K. Dick was utterly fascinating, looking at another person Miller would have found intriguing. Also on the topic of writers, Melville’s Bibles by Ilana Pardes spoke deeply to me.

For fiction, highly recommended are Amy Tomson’s The Color of Distance, Peter Rock’s My Abandonment, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, Toni Morrison’s, The Bluest Eye, Pete Hamill’s Snow in August, and Jennifer McMahon’s The Winter People. Less profound, but thoroughly enjoyable were Jonathan L. Howard’s Carter and Lovecraft, and Jasper Fforde’s The Woman Who Died a Lot (reading anything by Jasper Fforde is time well spent). My childhood favorite, Lester del Rey’s Day of the Giants retains its magic.

According to Goodreads, I finished 106 this year. Along the way I finished the 2016 Modern Mrs. Darcy reading challenge. Many of the books were excellent, and this shortlist represents those that idiosyncratically stick out in my mind. Please participate in a show of hope for the future: make 2017 a year of reading.