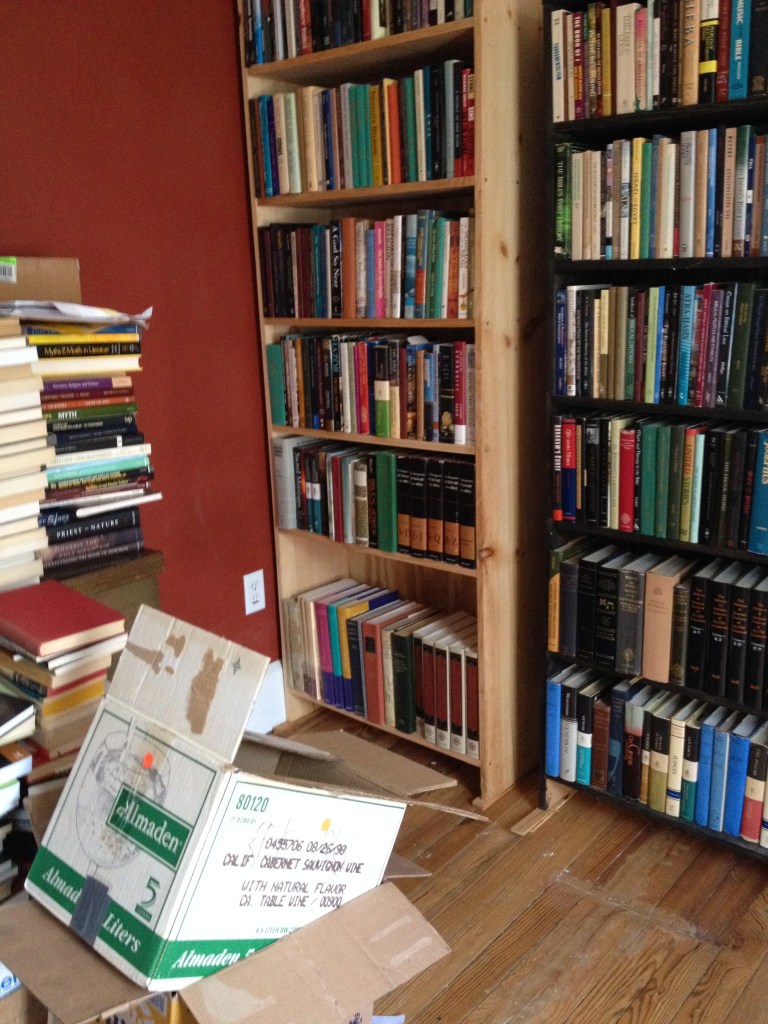

I’ve been thinking about moving lately. No, not planning to move, but just thinking about the process. A family member recently moved, and we have new neighbors in the house next to ours that sat empty for a few months. In both these cases the people moving are young and, I sincerely hope, optimistic. Settling into a new place takes quite a lot of energy and pondering my own life, a serious motivation. It wasn’t so hard when I was young and all I had acquired were books and records. After moving to college I ended up shifting around quite a bit, each time looking for a better fit. I moved five times in my three years in Boston. When I moved to Ann Arbor to be with my betrothed, and then wife, I moved twice in a year. Then in Scotland, three times within three years. Each move was optimistic.

Back in the States, we moved four times in three years until we ended up in the house Nashotah, well, House provided. That was our home for a decade or so and the move was optimistic. Something happened after that, however. The move from Nashotah was a step down. And the move from the first apartment to the second was another step down. Neither were optimistic moves. They were middle-of-life, disrupted-life moves. The perspective was hoping nothing tragic would happen. The move to New Jersey was quasi-optimistic. It was very difficult for me to give up my dream of a teaching career—something I had, and then lost. Still, our place, a floor of a two-family house, was good enough for a dozen years. Our last move, to our own house, was optimistic but fraught.

Home ownership is a shock to the system best absorbed by the young. To make matters more interesting, I recently talked to somebody who knows about finance who said buying property isn’t always the best investment. He urged us to go back to renting. I have a hard time imagining that now. Landlords are their own species of problem. Yes, we’re responsible for repairs and insurance, and lately lots of snow shoveling, but we don’t have an owner telling us what we can’t do. (Having finances tell us what we can’t do is another matter.) I always look fondly on the young who move, trying to tap into their optimism. This place, I very much hope, is better than the last one was. There is no perfect place to live, I know, but when you start thinking about it, it should be a matter of hope. And hope should be in greater supply these days.