One of the constant enjoyments of teaching is the interactive learning that takes place. I tell my students that I learn from them just as they learn (hopefully) from me. One place this has been happening regularly is in an Ancient Near Eastern Religions class I teach. Students have to provide weekly class reports on somewhat obscure deities that I chose for them to research. One of the groups was assigned Bes, the minor Egyptian protective deity, and their research had uncovered the suggestion that Bes may have originally been a cat-deity. As Halloween approaches with its plethora of black cats, I found this connection to be fascinating.

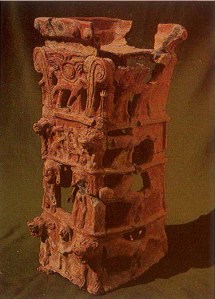

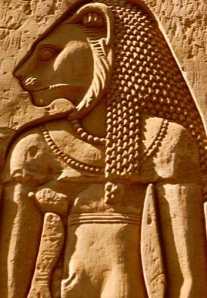

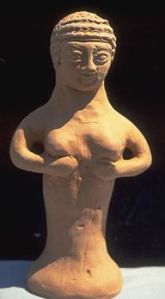

The Egyptians domesticated the cat, and revered it. The nimble catcher of vermin (although, in all fairness, vermin are only doing what vermin have evolved to do), the cat was seen as a protector. When in need, why not call upon a deified cat, an everlasting cat, if you will? It makes sense that Bes with his stubby proportions and bewhiskered face, often portrayed poking his tongue out, might have evolved from a feline original. His iconography often features leonine imagery as well. We may never know his true origins, but Bes was widely recognized in the ancient world as an effective protector.

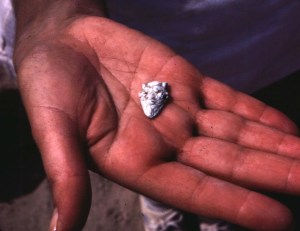

Back in 1987 I volunteered as a digger at Tel Dor in Israel. This was my first exposure to archaeology, and I loved every bit of it. The digging, the expectation of discovery, the honest physical work, the endless bouts of Herod’s revenge — well, some parts were better than others. One of the artifacts I discovered was a sky-blue faience head of Bes intended, apparently, to be worn on a necklace (there is a hole drilled through his head). I also found two bronze seed-beads that went with the necklace in the same matrix. Often I have wondered who, in an Israelite context, wore that amulet of Bes and what fate befell the wearer nevertheless. Bes is paradigmatic of our trust in help from beyond, but every once in a while even Bes ends up being dropped in the dirt only to be dragged out again by some future cat.