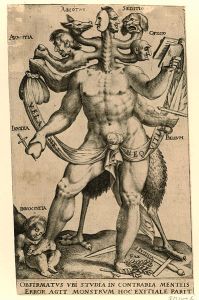

Once upon a time fairy tales were considered appropriate only for children. Unlike myths, fairy tales are frequently oral (yes, there are oral myths but this is not the place to discuss technicalities) and have origins that are obscure. A friend recently sent me a story entitled “Phylogenetic analyses suggests fairy tales are much older than thought” by Bob Yirka on phys.org. Using phylogenetic analysis, researchers have traced some fairy tales back thousands of years, into the Bronze Age of the ancient Near East. This will no doubt surprise some analysts who supposed fairy tales were a more recent, European invention. The tales change with time and distance, no doubt, but the basic story is very deeply rooted in who people are. Fairy tales are adult fare, after all.

I tried to make this point in an academic article that was rudely rejected by the journal Folklore some years back. I mean “rudely” literally. I’ve had academic articles rejected before—many of us have—but the letter that came with this one was insulting. My “error”? Suggesting that the story of the musician who travels to the underworld came from ancient Sumer. The article had its origins in my wife’s reading of the Mabinogion. The story of Bran’s head being washed down the river still singing reminded me of an Edinburgh ghost story the tour guides used to tell right outside our window. You’ve probably heard similar: a tunnel is discovered, a musician (a bagpiper, since this was Scotland) is sent down while playing so that those above can follow the sound, but the musician never emerges. I traced the story through the Celtic tradition of Uamh ‘n Òir, the cave of gold, through Bran, Orpheus, and finally back to Ishtar’s descent into the underworld. It was a fun piece, but serious. It ended up published in a Festschrift to a scholar with a noted sense of humor.

The fact is, traditional stories often go back very far in history. We haven’t the tools to trace many, nor can the results be taken for Gospel, but the implications can. People are storytellers by nature. We find meaning in what would today be called “fiction.” Too often I’ve had to hang my head in embarrassment when admitting to a fellow academic that I read (and sometimes write) fiction. It is something, however, that ancient mythographers and folklore singers would have understood. We can be academic some of the time, but we are human full-time. And telling stories is something that predates even the Bronze Age. Of that we can be completely certain. And they lived happily ever after.