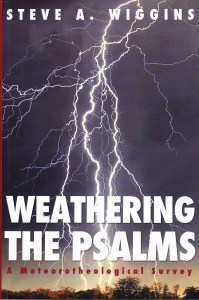

So the government’s shut down over a presidential temper tantrum. Like most people, I suspect, I haven’t really noticed. Except for two things. When I drove up to Ithaca over the holidays, some of the highway rest stops were closed. It seems our government wants to share the misery of not being able to relieve itself. Secondly, the NOAA weather forecasts are no longer updated as frequently as they should be. I’m no expert on the weather—I did write a book on meteorotheology, which took quite a bit of research on weather in ancient times, but I know that doesn’t qualify. Still, I rely on weather forecasts to get daily business done. In particular, we were expecting a winter storm around here that had been predicted, by NOAA, to arrive around 11 p.m.

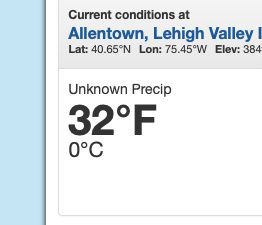

Okay, I thought, people will be off the roads by then, and crews will be out to treat the icy conditions by morning. Seven hours early, around 4 p.m., I noticed a rain, sleet, snow mix falling. The ice particles looked quite a lot like salt crystals, but I was pretty sure that the government doesn’t have that kind of pull. In any case, when weather catches me unawares, I turn to NOAA since our government is apparently God’s own chosen one, figuring that the Almighty might know a thing or two about what goes on upstairs. The current conditions, NOAA said, were “unknown precipitation.” Apparently the government isn’t even allowed to look out the window during a shut-down. Maybe it was salt after all.

So, among those of the “God of the gaps” crowd, the weather is perhaps the last refuge of a dying theology. Their cheery refrain of “science can’t explain” has grown somewhat foreshortened these last few decades, but when unknown precipitation is falling outside all bets are off. Come to think of it, Weathering the Psalms could’ve been titled Unknown Precipitation, but it’s a little late for that now. A creature long of habit, I awoke just after 3 a.m. Hastily dressing against the chill of the nighttime thermostat setting, I wandered to the window, wondering whether there would be a snow day. It’s dark this time of night, as I well know, but in the streetlights’ glow it seemed as if no weather event had happened at all. It’s just like our shut-down government to get such basic things wrong. As long as I’m up, I might as well get to work on my current book on horror. It’s only fitting.