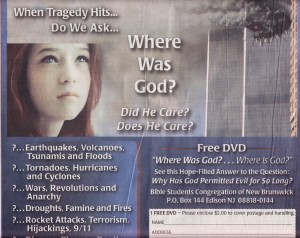

The Fundamentalist mouth has no filter. I’m a bit surprised by the furor raised by Phil Robertson’s comments about race and sexuality. Did A&E not realize that it was dealing with a Fundamentalist family on Duck Dynasty? I’m frequently amazed at how Fundamentalism is exoticised by the media as some quaint, back-woodsy phenomenon. Do they not realize that similar views are held by several members of congress and the pre-Obama presidential incumbent? By the numbers, Fundamentalism is a powerful force, but, like our universities, the media can’t be bothered to try to understand religion until a large demographic is suddenly threatened. A&E supports equality across sexual orientations, and, as it should go without saying in the twenty-first century, races. Prejudices, however, run very deep. Perhaps it’s just not so surprising to me, having been raised in a Fundamentalist environment. There was nothing exotic about it. It was, as we understood it, simple survival.

Phil Robertson has been suspended from his own show for comments made off-air. Wealth does not necessarily make one a better person. In fact, the figures trend in the other direction all too often. If instead of just promoting books written by the stars of the anatine series, the studio executives read those books they might have foreseen something like this coming. The Fundamentalist mind, I know from experience, tends to see things as black or white. Despite the camo, gray is a loathed color. Rainbow is even worse. The Fundamentalist psyche is not encouraged to try to see things from the other’s point of view. There is only one perspective: the right one. And when asked a straightforward question, a straightforward, if misguided answer will be given. It’s the price of fame.

The Robertson family, according to CNN, has closed ranks with their founder, claiming he is a godly man. There’s no irony here, folks. Fundamentalism isn’t into irony or subtle possibilities. Religious rights and freedoms are being press-ganged to the aid of those who long to speak free. Not about ducks, or guns, or calls. But about the naturalness of white skin and heterosexual love. And the Bible as the only possible source of the truth. The media often treats Fundamentalism as if it were a game, turned on or off at a whim. In reality it is a comprehensive worldview in which the inmates are commanded to speak the truth. The filters are not on their mouths, but are in their minds. Until we can learn to take them seriously, no duck anywhere will be safe.