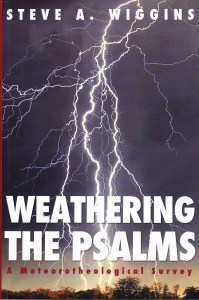

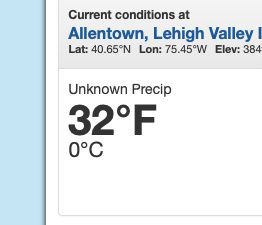

There’s a Ray Bradbury story—I can’t recall the title, but with the Internet that’s just a lame excuse—where explorers on Venus are being driven insane by the constant tapping of rain on their helmets. They try to concentrate on discovery, but the distraction becomes too much for them. Living in Pennsylvania has been a bit like that. I grew up in the state and I knew it rained a lot. Here in the eastern end we’ve hardly since the sun since March. And when you’ve got a leak in your roof that only compounds the problem. If I were weathering the Psalms, mine would be a lament, I’m afraid. You see, the ground’s squishy around here. Mud all over the place. Rivers have been running so high that they’re thinking about changing their courses. And still it rains.

There’s a lesson to be taken away from all this. The fact that we use water for our own ends sometimes masks the fact that it’s extremely powerful. Not tame. The persistence of water to reach the lowest point contributes to erosion of mountains and valleys. Its ease of transport which defines fluidity means that slowly, over time, all obstacles can be erased. It’s a lesson in which we could stand to be schooled from time to time. Rain is an artist, even if it’s making its way through the poorly done roofing job previous occupants put into place. Would we want to live in a world without valleys and pleasant streams? And even raging rivers?

There’s no denying that some of us are impacted by too much cloudiness. When denied the sun it becomes easy to understand why so many ancient people worshipped it. Around here the temperatures have plummeted with this current nor-easter and the heat kicked back on. Still, it’s good to be reminded that mother nature’s in control. Our high officials have decided global warming’s just alright with them, and we’re warned that things will grow much more erratic than this. As I hear the rain tapping on my roof all day long, for days at a time, I think of Bradbury’s Venus. Okay, so the story’s appropriately called “The Long Rain” (I looked it up). Meanwhile tectonic forces beneath our feet are creating new mountains to add to the scene. Nature is indeed an artist, whether or not our species is here to appreciate it. If it is, it might help to bring an umbrella this time around.